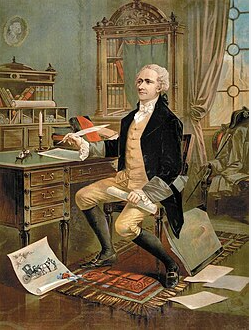

Human Nature is Against a Plurality in the Executive: Thoughts by Alexander Hamilton, Federalist 70

Men often oppose a thing merely because they have had no agency in planning it, or because it may have been planned by those whom they dilike.

In constructing the Executive Branch, some suggested that there should be a plurality in the Executive, much like the consulship in Rome. The plurality proposal was rejected in the Convention but, because of opposition by the Anti-Federalists, Alexander Hamilton defended unity in the Executive as the best way to have "energy" in the office.

Interestingly, in defending unity in the Executive, Hamilton made the following observations about human nature and interactions.

August Glen-James, editor

Wherever two or more persons are engaged in anyt common enterprise or pursuit, there is always danger of difference of opinion. If it be a public trust or office in which they are clothed with equal dignity and authority, there is peculiar danger of personal emulation and even animosity. From either, and especially from all these causes, the most bitter dissensions are apt to spring. Whenever these happen, they lessen the respectability, weaken the authority, and distract the plans and operations of those whom they divide. If they should unfortunately assail the supreme executive magistracy of a country, consisting of a plurality of persons, they might impede or frustrate the most important measures of the government in the most critical emergencies of the state. And what is still worse, they might split the community into the most violent and irreconcilable factions, adhering to the different individuals who composed the magistracy.

Men often oppose a thing merely because they have had no agency in planning it, or because it may have been planned by those whom they dilike. But if they have been consulted, and have happened to disapprove, opposition then becomes, in their estimation an indispensable duty of self-love. They seem to think themselves bound in honor, and by all the motives of personal infallibility, to defeat the success of what has been resolved upon, contrary to their sentiments. Men of upright, benevolent tempers have too many opportunities of remarking, with horror, to what desperate lengths this disposition is sometimes carried, and how often the great interests of society are sacrificed to the vanity, to the conceit, and to the obstinancy of individuals, who have credit enough to make their passions and their caprices interesting to mankind. Perhaps the question now before the public may, in its consequences, afford melancholy proofs of the effects of this despicable frailty, or rather detestable vice, in the human character.