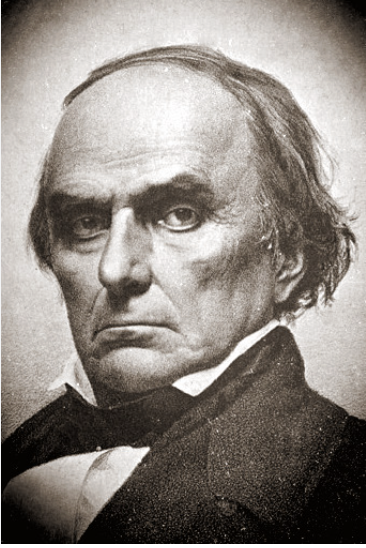

"Reform of the Naturalization Laws": A speech by Daniel Webster, 1844.

There is not the slightest doubt that in numerous cases different persons vote on the strength of the same set of naturalization papers . . .

In November 1844, Democrat James K. Polk defeated Whig candidate, Henry Clay, for the presidency. This was a hard pill to swallow for Daniel Webster, who claimed that Polk won because of fraudulent votes by speedily "naturalized" citizens in Pennsylvania and New York.

Webster believed that lax enforcement of naturalization laws made it possible for vote-needing politicians to illegally "naturalize" immigrants almost as soon as they docked in country. He gave this speech to the Boston Whigs, 1844.

Here are his thoughts.

August Glen-James, editor

The result of the recent elections in several states has impressed my mind with one deep and strong conviction: that is, that there is an imperative necessity for reforming the naturalization laws of the United States. The preservation of the government, and consequently the interest of all parties, in my opinion, clearly and strongly demand this.

All are willing and desirous, of course, that America should continue to be the safe asylum for the oppressed of all nations. All are willing and desirous that the blessings of a free government should be open to the enjoyment of the worthy and industrious from all countries who may come hither for the purpose of bettering their circumstances by the successful employment of their own capital, enterprise, or labor. But it is not unreasonable that the elective franchise should not be exercised by a person of a foreign birth until after such a length of residence among us as that he may be supposed to have become, in some good measure, acquainted with our Constitution and laws, our social institutions, and the general interest of the country; and to have become an American in feeling, principle, character, and sympathy, as well as by having established his domicile among us.

Those already naturalized have, of course, their rights secured; but I can conceive no reasonable objection to the different provision in regard to future cases. It is absolutely necessary, also, in my judgment, to provide new securities against the abominable frauds, the outrageous, flagrant perjuries which are notoriously perpetrated in all the great cities. There is not the slightest doubt that in numerous cases different persons vote on the strength of the same set of naturalization papers; there is as little doubt that immense numbers of such papers are obtained by direct perjury; and that these enormous offenses multiply and strengthen themselves beyond all power of punishment and restraint by existing provisions.

I believe it to be an unquestionable fact that masters of vessels, having brought over immigrants from Europe, have, within thirty days of their arrival, seen those persons carried up to the polls and give their votes for the highest offices in the national and state governments. Such voters, of course, exercise no intelligence and, indeed, no volition of their own. They can know nothing either of the questions in issue or of the candidates proposed. They are mere instruments used by unprincipled and wicked men, and made competent instruments only by the accumulation of crime upon crime.

Now it seems to me impossible that every honest man and every good citizen, every true lover of liberty and the Constitution, every real friend of the country, would not desire to see an end put to these enormous abuses. I avow it, therefore, as my opinion that it is the duty of us all to endeavor to bring about an efficient reformation of the naturalization laws of the United States.

I am well aware, gentlemen, that these sentiments may be misrepresented, and probably will be, in order to excite prejudice in the mind of foreign residents. Should such misrepresentations be made or attempted, I trust to my friends to correct it and expose it. For the sentiments themselves I am ready to take to myself the responsibility, and I will only add that what I have now suggested is just as important to the rights of foreigners, regularly and fairly naturalized among us, as to the rights of native-born American citizens. [The whole assembly here united in giving twenty-six tremendous cheers.]

The present condition of the country imperatively demands this change. The interest, the real welfare of all parties, the honor of the nation all require that subordinate and different party questions should be made to yield to this great end. And no man who esteems the prosperity and existence of his country as of more importance than fleeting party triumph will or can hesitate to give in his adherence to these principles. [Nine cheers.]

Gentlemen, there is not a solitary doubt that if the elections have gone against us it has been through false and fraudulent votes. Pennsylvania, if, as they say, she has given 6,000 for our adversaries, has done so through the basest fraud. Is it not so? And look at New York. In the city there were thrown 60,000 votes, or one vote to every five inhabitants. You know that, fairly and honestly, there can be no such thing on earth. [Cheers.] And the great remedy is for us to go directly to the source of true popular power and to purify the elections. [Twenty-six cheers.]

Fellow citizens, I profess to be a lover of human liberty, especially to be devoted to the grand example of freedom set forth by the republic under which we live. But I profess my heart, my reputation, my pride of character, to be American.

Source: John P. Sanderson, Republican Landmarks: The Views and Opinions of American Statesmen on Foreign Immigration, Philadelphia, 1856, pp. 323-324. Quoted in The Annals of America, pp. 168-169.