Defining the Union: Views from the North and South via William Russell, 1861.

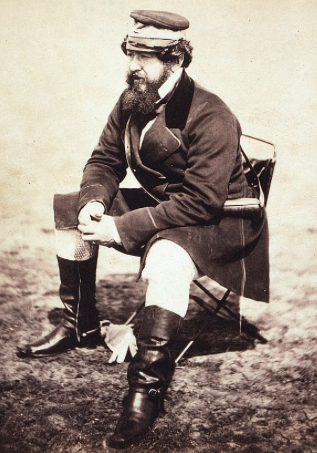

William Russell was an Irish reporter for The Times. He is considered to be one of the first war correspondents having reported, for instance, on the Crimean War. He happened to be in the United States when the Civil War was beginning and wrote several letters with interesting observations.

The context of this selection is the view of the American Union from an outside perspective for an outside audience. The content of his observation was a major point of contention between the North and the South.

August Glen-James, editor

We, it appears, talked of American citizens when there were no such beings at all. There were, indeed, citizens of the Sovereign State of South Carolina, or of Georgia or Florida, who permitted themselves to pass under that designation, but it was merely as a matter of personal convenience.

I am desirous of showing in a few words, for the information of the English readers, how it is that the Confederacy which Europe knew simply as a political entity has succeeded in dividing itself. The Slave States held the doctrine, or say they did, that each State was independent as France or as England, but that for certain purposes they chose a common agent to deal with foreign nations, and to impose taxes for the purpose of paying the expenses of the agency. We, it appears, talked of American citizens when there were no such beings at all. There were, indeed, citizens of the Sovereign State of South Carolina, or of Georgia or Florida, who permitted themselves to pass under that designation, but it was merely as a matter of personal convenience. It will be difficult for Europeans to understand this doctrine, as nothing like it has been heard before, and no such Confederation of Sovereign States has ever existed in any country in the world.

The Northern men deny that it existed here, and claim for the Federal Government powers not compatible with such assumptions. They have lived for the Union, they served it, they labored for and made money by it. A man as a New York man was nothing—as an American citizen he was a great deal. A South Carolinian objected to lose his identity in any description which included him and a “Yankee clockmaker” in the same category. The Union was against him; he remembered that he came from a race of English gentlemen who had been persecuted by the representatives—for he will not call them the ancestors—of the Puritans of New England, and he thought that they were animated by the same hostility to himself. He was proud of old names, and he felt pleasure in tracing his connection with old families in the old country. His plantains were held by old charters, or had been in the hands of his fathers for several generations; and he delighted to remember that when the Stuarts were banished from their throne and their country, the burgesses of South Carolina had solemnly elected the wandering Charles king of their State, and had offered him an asylum and a kingdom.

“State Rights!” To us [i.e., the British] the question is simply inexplicable or absurd. And yet thousands of Americans sacrifice all for it.