Ideological Unity & Communism: Thoughts by Milovan Djilas

Once ideological unity is established, it operates as powerfully as prejudice.

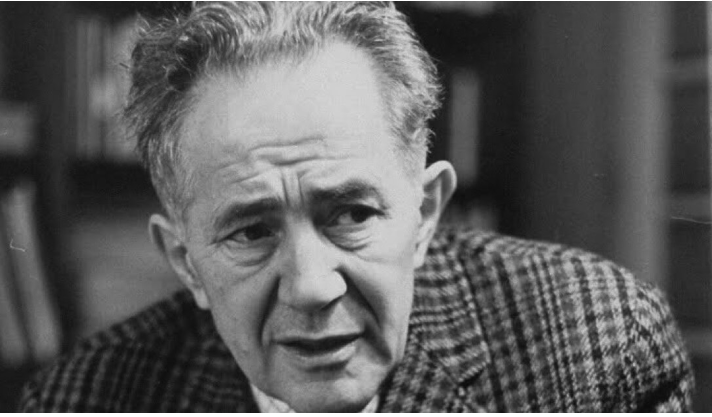

Milovan Djilas became a communist revolutionary in Yugoslavia and was a true believer in communist doctrine. However, he became disillusioned by its practice--especially in the USSR--and finally became a powerful critic. His criticism was not so much with socialist doctrine; rather, he came to be an inveterate critic of communist parties and their transformation from revolutionaries promising the end of exploitation to becoming exploiters themselves.

In this excerpt, Djilas writes about the concept, importance, and use of "ideological unity" in communism.

August Glen-James, editor

But this is the inescapable road of every Communist system. The method of establishing totalitarian control, or ideological unity, may be less severe than Stalin’s, but the essence is always the same.

The obligatory ideological unity of the party . . . has remained the most essential characteristic of Bolshevik or Communist parties. . . Except for the Communist bureaucracy, not a single class or party in modern history has attained complete ideological unity. None had, before, the task of transforming all of society, mostly through political and administrative means. For such a task, a complete fanatical confidence in the righteousness and nobility of their views is necessary. Such a task calls for exceptionally brutal measures against other ideologies and social groups. It also calls for ideological monopoly over society and for absolute unity of the ruling class. Communist parties have needed special ideological solidarity for this reason.

Once ideological unity is established, it operates as powerfully as prejudice. Communists are educated in the idea that ideological unity, or the prescription of ideas from above, is the holy of holies, and that factionalism in the party is the greatest of all crimes. . . . In fact, Stalin knew that Trotsky, Bukharin, Zinoviev, and others were not foreign spies and traitors to the “socialist fatherland.” However, since their disagreement with him obviously delayed the establishment of totalitarian control, he had to destroy them. His crimes with the party consist of the fact that he transformed “objective unfriendliness”—the ideological and political differences in the party—into the subjective guilt of groups and individuals, attributing to them crimes which they did not commit. . . . But this is the inescapable road of every Communist system. The method of establishing totalitarian control, or ideological unity, may be less severe than Stalin’s, but the essence is always the same.