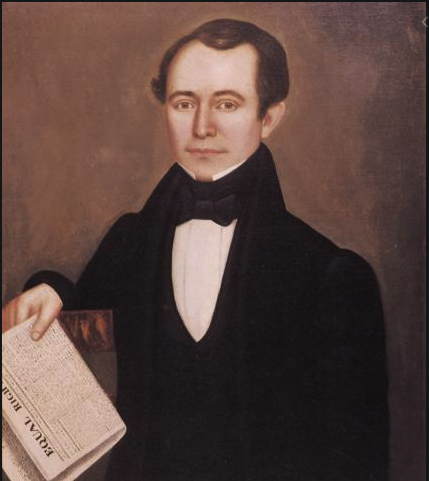

John Marshall and the Supreme Court: Thoughts by William Leggett, July 28, 1835

Chief Justice John Marshall died July 6, 1835. After paying homage to Marshall’s patriotism, intellect, and contributions to the country, William Leggett wrote an editorial wherein he duly mourned Marshall’s passing and then brought his observations to this point: “The enormous powers of the Supreme tribunal of the country will no longer be exercised by one whose cardinal maxim in politics inculcated distrust of popular intelligence and virtue, and whose constant object, in the decision of all constitutional questions, was to strengthen government at the expense of the people’s rights.”

Leggett expounded on this premise in the rest of his editorial. As readers will see, Leggett addresses the centralizing tendency in certain political "creeds," as well held, in Leggett's opinion, by Chief Justice John Marshall.

August Glen-James, editor

But sincerely believing that the principles of democracy are identical with the principles of human liberty, we cannot but experience joy that the chief place in the supreme tribunal of the Union will no longer be filled by a man whose political doctrines led him always to pronounce such decision of Constitutional questions as was calculated to strengthen government at the expense of the people.

There is no journalist who entertained a truer respect for the virtues of Judge Marshall than ourselves; there is none who believed more fully in the ardour of his patriotism, or the sincerity of his political faith. But according to our firm opinion, the articles of his creed, if carried into practice, would prove destructive of the great principle of human liberty, and compel the many to yield obedience to the few. The principles of government entertained by Marshall were the same as those professed by Hamilton, and not widely different from those of the elder Adams. That both these illustrious men, as well as Marshall, were sincere lovers of their country, and sought to effect, through the means of government, the greatest practicable amount of human happiness and prosperity, we do not entertain, we never have entertained a doubt. Nor do we doubt that among those who uphold the divine right of kings, and wish to see a titled aristocracy and hierarchy established, there are also very many solely animated by a desire to have a government established adequate to self-preservation and the protection of the people. Yet if one holding a political creed of this kind, and who, in the exercise of high official functions, had done all in his power to change the character of the government from popular to monarchical, should be suddenly cut off by death, would it be unjustifiable in those who deprecated his opinions to allude to them and their tendency, while paying a just tribute to his intellectual and moral worth?

Of Judge Marshall’s spotless purity of life, of his many estimable qualities of heart, and of the powers of his mind, we record our hearty tribute of admiration. But sincerely believing that the principles of democracy are identical with the principles of human liberty, we cannot but experience joy that the chief place in the supreme tribunal of the Union will no longer be filled by a man whose political doctrines led him always to pronounce such decision of Constitutional questions as was calculated to strengthen government at the expense of the people. We lament the death of a good and exemplary man, but we cannot grieve that the cause of aristocracy has lost one of its chief supports.