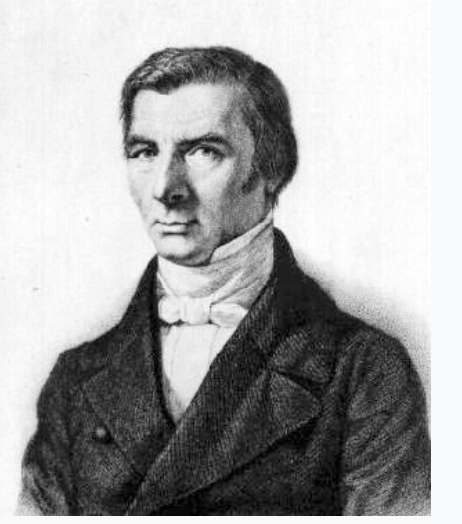

"Property and Law:" Thoughts by Frédéric Bastiat, 1848.

Introduction:

This essay was originally published May 15, 1848, in Le Journal des économistes.

The utility of Frédéric Bastiat’s essay, from which this excerpt comes, is found in the philosophical contrast between an individualist and collectivist world view concerning Property and Law.

For brevity’s sake (although more complex than what is presented here), the fundamental difference, as characterized by Bastiat, between an individualist and a collectivist was essentially that the former believed in the primacy of the individual in society. In this world view, society and government served to protect the individual’s natural rights to life, liberty, and property. This world view called for the power of government to be limited to the negative role of protecting one’s natural rights. This position fit like a hand in the glove of Capitalism.

In the latter worldview, the individual was to serve the collective needs of the society as envisioned and positively promoted by the legislator. This position was the ethos of socialism, which Bastiat opposed. To set up his opponents’ basic arguments, he quoted, for instance, Jean-Jacque Rousseau thusly:

He who dares undertake to provide institutions to a people must feel that he is capable, so to speak, of changing human nature, of transforming each individual who, of himself is a perfect and solitary whole, into a part of a much greater whole from which this individual is to receive to a certain degree his life and being; of changing the physical constitution of man in order to strengthen it. . . .

Bastiat believed the “legislator” had no such office. Moreover, Bastiat wrote: “According to [Rousseau], the law ought to transform people and create or not create property. According to me, society, people, and property existed before the laws, and, to limit myself to a particular question, I would say: It is not because there are laws that there is property, but it is because there is property that there are laws.”

This is sufficient background to scaffold this excerpt.

August Glen-James, editor

Let us never forget that, in fact, the state has no resources of its own. It has nothing, it possesses nothing that it does not take from the workers. When, then, it meddles in everything, it substitutes the deplorable and costly activity of its own agents for private activity.

Did we not hear, right in the middle of the nineteenth century, a few days after the February Revolution (a revolution made in the name of liberty) a man, more than a cabinet minister, actually a member of the provisional government, a public official vested with revolutionary and unlimited authority, coolly inquire whether in the allotment of wages it was good to consider the strength, the talent, the industriousness, the capability of the worker, that is, the wealth he produced; or whether, in disregard of these personal virtues or of their useful effect, it would not be better to give everyone henceforth a uniform remuneration?

This is tantamount to asking: Will a yard of cloth brought to market by an idler sell at the same price as two yards offered by an industrious man? And, what passes all belief, this same individual proclaimed that he would prefer profits to be uniform, whatever the quality or the quantity of the product offered for sale, and he therefore decided in his wisdom that, although two are two by nature, they are to be no more than one by law.

This is where we get when we start from the assumption that the law is stronger than nature.

Those whom he addressed apparently understood that such arbitrariness is repugnant to the very nature of man, that one yard of cloth could never be made to give the right to the same remuneration as two yards. In such a case, the competition that was to be abolished would be replaced by another competition a thousand times worse: each worker would strive to be the one who worked the least, who exerted himself the least, since, by law, the wage would always be guaranteed and would be the same for all.

However, Citizen Blanc had foreseen this objection, and, to prevent this sweet-do-nothing, alas so natural in man when his work is not remunerated, he thought of the idea of erecting in each commune a post where the names of the idlers would be inscribed. But he did not say whether there would be inquisitors to spy out the sin of laziness, tribunals to judge it, and police to carry out the sentence. It is to be noted that the utopians are never concerned with the vast governmental apparatus that alone can set their legal mechanism in motion.

When the delegates of the Luxembourg appeared a bit incredulous, up strode Citizen Vidal, the secretary of Citizen Blanc, to add the finishing touches to the thought of the master. Following Rousseau's example, Citizen Vidal proposed nothing less than to change human nature and the laws of Providence.

It has pleased Providence to give to every individual certain needs and their consequences, as well as certain faculties and their consequences, thus creating self-interest, otherwise known as the instinct for self- preservation and the desire for self-development, as the great motive force of mankind. M. Vidal is going to change all this. He has looked at the work of God, and he has seen that it was not good. Consequently, proceeding from the principle that the law and the legislator can do anything, he will be abolishing personal interest by decree and replacing it by point of honor.

Men will no longer work to live, to provide for and raise their families, but to obey a point of honor, to avoid the hangman’s noose, as though this new motive were not still a personal interest of another kind.

M. Vidal constantly refers to what the question of honor encourages armies to do. But alas! Everything must be stated clearly, and if the wish is to regiment workers we should be told whether the military code, with its thirty transgressions carrying the death penalty, would become the labor code!

An even more striking effect of the harmful principle that I am here seeking to combat is the uncertainty that it always holds suspended, like the sword of Damocles, over labor, capital, commerce, and industry; and this is so serious that I venture to ask the reader to give his full attention to it.

In a country like the United States, where the right to property is placed above the law, where the sole function of the public police force is to safeguard this natural right, each person can in full confidence dedicate his capital and his labor to production. He does not have to fear that his plans and calculations will be upset from one instant to another by the legislature.

But when, on the contrary, acting on the principle that not labor, but the law, is the basis of property, we permit the makers of utopias to impose their schemes on us in a general way and by decree, who does not see that all the foresight and prudence that Nature has implanted in the heart of man is turned against industrial progress?

Where, at such a time, is the bold speculator who would dare set up a factory or engage in an enterprise? Yesterday it was decreed that he will be permitted to work only for a fixed number of hours. Today it is decreed that the wages of a certain type of labor will be fixed. Who can foresee tomorrow's decree, that of the day after tomorrow, or those of the days following? Once the legislator is placed at this incommensurable distance from other men, and believes, in all conscience, that he can dispose of their time, their labor, and their transactions, all of which are their property, what man in the whole country has the least knowledge of the position in which the law will forcibly place him and his line of work tomorrow? And, under such conditions, who can or will undertake anything?

I certainly do not deny that among the innumerable systems that this false principle gives rise to, a great number, the greater number even, originate from benevolent and generous intentions. But what is vicious is the principle itself. The manifest end of each particular plan is to equalize prosperity. But the still more manifest result of the principle on which these plans are founded is to equalize poverty; nay more, the effect is to force the well-to-do families down into the ranks of the poor and to decimate the families of the poor by sickness and starvation.

I confess that I fear for the future of my country when I think of the seriousness of the financial difficulties that this dangerous principle will aggravate still further.

Nor is this all. The public has been deluged, with an unlimited prodigality, by two sorts of promises. According to one, a vast number of charitable, but costly, institutions are to be established at public expense. According to the other, all taxes are going to be reduced. Thus, on the one hand, nurseries, asylums, free primary and secondary schools, workshops, and industrial retirement pensions are going to be multiplied. Slave owners are going to be paid indemnities, and the slaves themselves are to be paid damages; the state is going to found credit institutions, lend to workers the tools of production, double the size of the army, reorganize the navy, etc., etc., and, on the other hand, it will abolish the tax on salt, tolls, and all the most unpopular excises.

Certainly, whatever idea one may have of France's resources, it will at least be admitted that these resources must be developed in order to be adequate for this double enterprise, so gigantic and apparently so contradictory.

But here, in the midst of this extraordinary movement, which may be considered as above the power of man to accomplish, at the same time as all the energies of the country are being directed toward productive labor, a cry arises: The right to property is a creation of the law. Consequently, the legislator can promulgate at any time, in accordance with whatever theories he has come to accept, decrees that may upset all the calculations of industry. The worker is not the owner of a thing or of a value because he has created it by his labor, but because today's law guarantees it. Tomorrow's law can withdraw this guarantee, and then the ownership is no longer legitimate.

What must be the consequence of all this? Capital and labor will be frightened; they will no longer be able to count on the future. Capital, under the impact of such a doctrine, will hide, flee, be destroyed. And what will become, then, of the workers, those workers for whom you profess an affection so deep and sincere, but so unenlightened? Will they be better fed when agricultural production is stopped? Will they be better dressed when no one dares to build a factory? Will they have more employment when capital will have disappeared?

And from what source will you derive the taxes? And how will you replenish the treasury? How will you pay the army? How will you meet your debts? With what money will you furnish the tools of production? With what resources will you support these charitable institutions, so easy to establish by decree?

I hasten to turn aside from these dreary considerations. It remains for me to examine the consequences of the principle opposed to that which prevails today, the economist's principle, the principle that derives the right to property from labor, and not from the law, the principle which says: Property is prior to law; the sole function of the law is to safeguard the right to property wherever it exists, wherever it is formed, in whatever manner the worker produces it, whether individually or in association, provided that he respects the rights of others.

First, whereas the jurists' principle involves virtual slavery, the economists' principle implies liberty. Property, the right to enjoy the fruits of one's labor, the right to work, to develop, to exercise one's faculties, according to one's own understanding, without the state intervening otherwise than by its protective action--this is what is meant by liberty. And I still cannot understand why the numerous partisans of the systems opposed to liberty allow the word liberty to remain on the flag of the Republic. To be sure, a few of them have effaced it in order to substitute the word solidarity. They are more honest and more logical. But they should have said communism, and not solidarity; for the solidarity of men's interests, like property, exists outside the purview of the law.

Moreover, it implies unity. This we have already seen. If the legislator creates the right to property, there are as many modes of property as there can be errors in the utopians' heads, that is, an infinite number. If, on the contrary, the right to property is a providential fact, prior to all human legislation, and which it is the function of human legislation to safeguard, there is no place for any other system.

Beyond this, there is security; and all evidence clearly indicates that, if people sincerely recognize the obligation of every person to provide his own means of existence, as well as every person's right to the fruits of his own labor as prior and superior to the law, if human law is needed and intervenes only to guarantee to all the freedom to engage in labor and the ownership of its fruits, then all human industry is assured a future of complete security. There is no longer reason to fear that the legislature may, with one decree after another, stifle effort, upset plans, frustrate foresight. Under the shelter of such security, capital will rapidly be created. The rapid accumulation of capital, in turn, is the sole reason for the increase in the value of labor. The working classes will, then, be well off; they themselves will co-operate to form new capital. They will be better able to rise from the status of wage earners, to invest in business enterprises, to found enterprises of their own, and to regain their dignity.

Finally, the eternal principle that the state should not be a producer, but the provider of security for the producers, necessarily involves economy and order in public finances; consequently, this principle alone renders prosperity possible and a just distribution of taxes.

Let us never forget that, in fact, the state has no resources of its own. It has nothing, it possesses nothing that it does not take from the workers. When, then, it meddles in everything, it substitutes the deplorable and costly activity of its own agents for private activity. If, as in the United States, it came to be recognized that the function of the state is to provide complete security for all, it could fulfill this function with a few hundred million francs. Thanks to this economy, combined with industrial prosperity, it would finally be possible to impose a single direct tax, levied exclusively on property of all kinds.

But, for that, we must wait until we have learned by experience --perhaps cruel experience--to trust in the state a little less and in mankind a little more.

[All italics in original. Editor.]