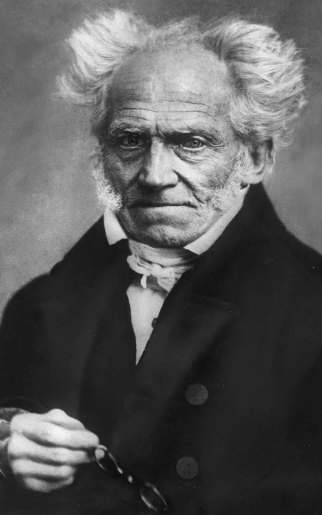

Reading and Thinking: Thoughts by Arthur Schopenhauer, 19th Century

This post offers some interesting ideas from the German philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer, about the nexus between reading and thinking.

The piece speaks for itself. Enjoy.

August Glen-James, editor

. . . the surest way of never having any thoughts of your own is to pick up a book every time you have a free moment.

As the biggest library if it is in disorder is not as useful as a small but well-arranged one, so you may accumulate a vast amount of knowledge but it will be of far less value to you than a much smaller amount if you have not thought it over for yourself; because only through ordering what you know by comparing every truth with every other truth can you take complete possession of your knowledge and get it into your power. You can think about only what you know, so you ought to learn something; on the other hand, you can know only what you have thought about.

Now you can apply yourself voluntarily to reading and learning, but you cannot really apply yourself to thinking: thinking has to be kindled, as a fire is by a draft, and kept going by some kind of interest in its object, which may be an objective interest or merely a subjective one. The latter is possible only with things that affect us personally, the former only to those heads who think by nature, to whom thinking is as natural as breathing, and these are very rare. That is why most scholars do so little of it.

The difference between the effect produced on the mind by thinking for yourself and that produced by reading is incredibly great, so that the original difference which made one head decide for thinking and another for reading is continually increased. For reading forcibly imposes on the mind thoughts that are as foreign to its mood and direction at the moment of reading as the signet is to the wax upon which it impresses its seal. The mind is totally subjected to an external compulsion to think this or that for which it has no inclination and is not in the mood. On the other hand, when it is thinking for itself it is following its own inclination, as this has been more closely determined either by its immediate surroundings or by some recollection or other: for its visible surroundings do not impose some single thought on the mind, as reading does; they merely provide it with occasion and matter for thinking the thoughts appropriate to its nature and present mood. The result is that much reading robs the mind of all elasticity, as the continual pressure of a weight does a spring, and that the surest way of never having any thoughts of your own is to pick up a book every time you have a free moment. The practice of doing this is the reason erudition makes most men duller and sillier than they are by nature and robs their writings of all effectiveness: they are in Pope’s words: For ever reading, never to be read.