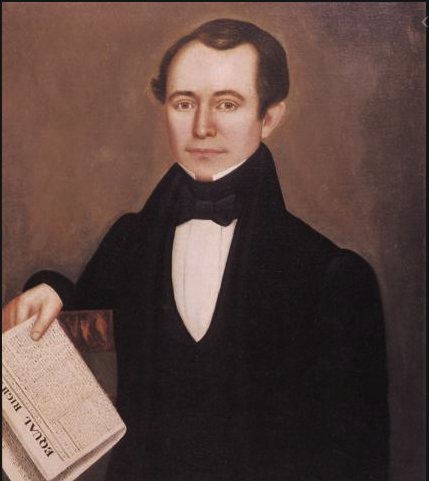

Revolutionary Pensioners: Thoughts by William Leggett, Dec. 8, 1834

In this selection, William Leggett was responding to a proposal by Assistant Alderman Tallmadge that one hundred dollars be “paid out of the city treasury on the 1st January next, to every surviving officer and soldier of the revolution in the city and county of New York, now receiving a pension, provided the number does not exceed one hundred.” Mr. Tallmadge had chosen a “very fine theme,” according to Leggett, but was providing for a “usurpation” of power not granted to the government. As such, the measure, Leggett believed, should be opposed.

William Leggett’s thinking on the subject, whether one agrees or disagrees, will give the reader something to think about concerning the role the government should play in society vis a vis the voluntary actions of individuals. In totality, it is clear that he believes that if the pensioners are owed anything, it should be by voluntary contributions rather than by force of government.

August Glen-James, editor

Every man ought to be his own almoner, and not suffer those whom he has elected for far different purposes, to squander the funds of the public chest, at any rate, and on any object which may seem to them deserving of sympathy. The precedent is a wrong one, and is doubly wrong, inasmuch as the general regard for those for whose benefit this stretch of power is exerted, may lead men to overlook the true character of the unwarrantable assumption.

Let us reflect a moment what this proposition is which the Board of Assistant Aldermen have, with this single exception, unanimously adopted. Why to give away ten thousand dollars of the people’s money to such of the revolutionary pensioners as reside in the city of New York. Does not the plain good sense of every reader perceive that this is a monstrous abuse of the trust confided to our city legislators? Did we send them to represent us in the Common Council that they may squander away the city’s treasures at such a lavish rate? Is it any part of their duty to make New-Year’s presents? Have they any right under heaven to express their sympathy for the revolutionary pensioners at the city’s cost? If they have, where is the warrant for it? Let them point their fingers to the clause in the city charter which authorizes them to lay taxes, that they may be expended again in bounties, rewards and largesses, to class any of the men whatever.

Let no reader suppose that in making these remarks, we lack proper appreciation of the eminent services rendered to this country, and to the cause of human liberty throughout the world, by those brave and heroic men who achieved our national independence. Doubtless many, very many of them, entered into that contest with no higher motives than animate the soldier in every contest, for whatsoever object undertaken—whether in defense of liberty or to destroy it. But the glorious result has spread a halo around all who had any share in achieving it, and they will go down together in history, to the latest hour of time, as a band of disinterested, exalted, incorruptible and invincible patriots. This is the light in which their sons, at least, the inheritors of their precious legacy of freedom, ought to view them; and they never, while a single hero of that band remains, can be exonerated from the obligations of gratitude which they owe. But we would not, on that account, authorize any usurpation of power by our public servants, under the presence of showing the gratitude of the community to the time-worn veterans of the revolutionary war.—Every man ought to be his own almoner, and not suffer those whom he has elected for far different purposes, to squander the funds of the public chest, at any rate, and on any object which may seem to them deserving of sympathy. The precedent is a wrong one, and is doubly wrong, inasmuch as the general regard for those for whose benefit this stretch of power is exerted, may lead men to overlook the true character of the unwarrantable assumption.

Let ten thousand—let fifty thousand dollars be given by our city to the revolutionary veterans who are closing their useful lives in the bosom of this community; but let it be given to them without an infringement of those sacred rights which they battled to establish. If the public feeing would authorize such a donation as Mr. Tallmadge exerted his “eloquence” in support of, that same feeling would prompt our citizens, each man for himself, to make personal contributions towards a fund which should properly and nobly speak the gratitude of New York towards the venerable patriots among them. But the tax-payer, who would liberally contribute to such an object, in a proper way, may very naturally object to Mr. Tallmadge thrusting his hand into his pocket, and forcing him to give for what and to whom that eloquent gentleman pleases. If the city owes an unliquidated amount, not of gratitude, but of money, to the revolutionary pensioners, let it be paid by the Common Council, and let Mr. Tallmadge be as eloquent as he pleases, or as he can be, in support of the appropriation. But beyond taking care of our persons and our property, the functions neither of our city government, nor of our state government, nor of our national government, extend. We hope to see the day when the people will jealously watch and indignantly punish every violation of this principle.

That what we have here written does not proceed from any motive other than that we have stated, we trust we need not assure our readers. That, above all, it does not proceed form any unkindness towards the remaining heroes of the revolution, must be very evident to all such as have any knowledge of the personal relations of the writer. Among those who would receive the benefit of Mr. Tallmadge’s scheme is the venerable parent of him whose opinions are here expressed. That parent, after a youth devoted to the service of his country, after a long life of unblemished honor, now, in the twilight of his age, and bending under the burden of fourscore years, is indebted to the tardy justice of his Government for much of the little light that cheers the evening of his eventful day. Wanting indeed should we be, therefore, in every sentiment of filial duty and love, if we could oppose this plan of a public donation, for any other than public and sufficient reasons. But viewing it as an attempt to exercise a power which the people never meant to confer upon their servants, we should be wanting in those qualities of which this donation is intended to express the sense of the community, if we did not oppose it. We trust the resolution will not pass the upper Board.