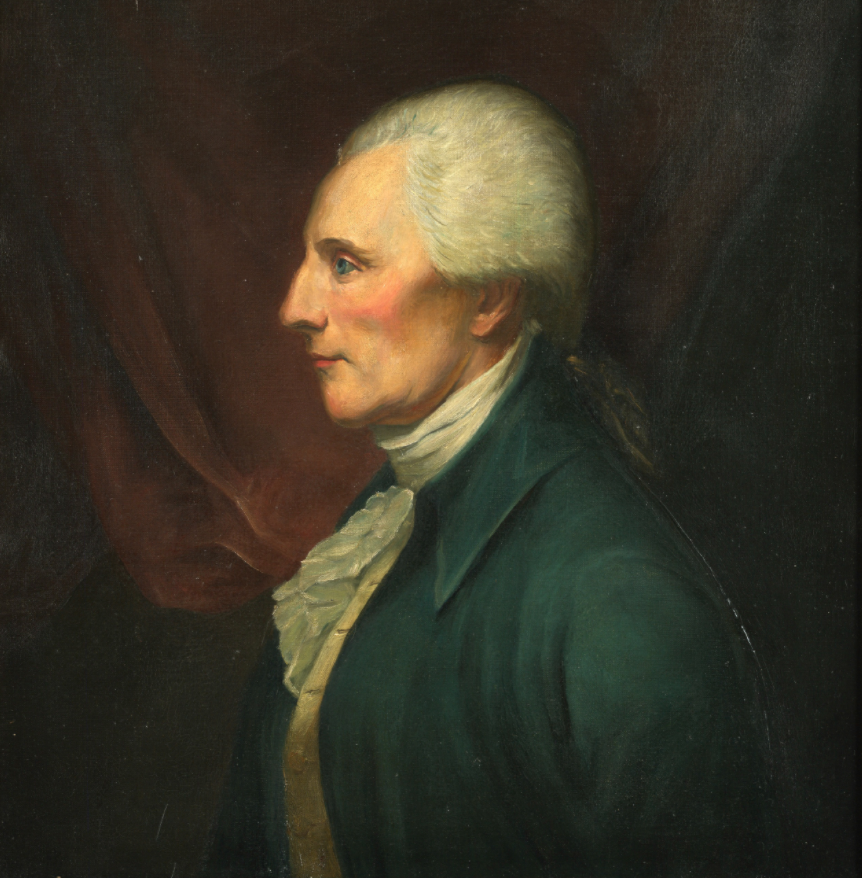

Sectionalism & A Silent Conspiracy: Thoughts by Richard Henry Lee, 1787

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee introduced a resolution for independence from Britain in the Continental Congress. Subsequent to this resolution, a committee was formed to write a declaration of causes for independence. As most know, Thomas Jefferson penned said declaration, took advice from committee members, John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, made some revisions, and submitted it to Congress on June 28, 1776. Congress debated the Declaration on July 1. On July 2, the Declaration was approved. Incidentally, John Adams surmised that July 2 would be the date future Americans would celebrate independence. On July 4, 1776, Congress approved a final draft. Most signatures on the document weren’t added until August 1776.

In this excerpt, Lee is writing to Edmund Randolph outlining his concerns about the proposed Constitution. It is of historical importance to understand the arguments that were offered against the Constitution by the Anti-Federalists. Randolph had been a delegate at the convention, but refused to endorse the plan. I have added some summaries in this post, as will be indicated below.

--August Glen-James, editor

It having been found from universal experience, that the most express declarations and reservations are necessary to protect the just rights and liberty of mankind from the silent, powerful and ever active conspiracy of those who govern . . .

The establishment of the new plan of government, in its present form, is a question that involves such immense consequences to the present times and to posterity, that it calls for the deepest attention of the best and wisest friends of their country and of mankind. If it be found good after mature deliberation, adopt it, if wrong, amend it at all events, for to say (as many do) that a bad government must be established for fear of anarchy, is really to say that we must kill ourselves for fear of dying.

Good government is not the work of a short time, or of sudden thought. From Moses to Montesquieu the greatest geniuses have been employed on this difficult subject, and yet experience has shewn capital defects in the system produced for the government of mankind. But since it is neither prudent or easy to make frequent changes in government, and as bad governments have been generally found the most fixed; so it becomes of the last consequence to frame the first establishment upon ground the most unexceptionable, and such as the best theories with experience justify; not trusting as our new constitution does, and as many approve of doing, to time and future events to correct errors, that both reason and experience in similar cases, point out in the new system.

[His list of errors/problems summarized]

- The different branches of the “legislature” should be unconnected and the legislative and executive powers should be separate. Lee writes, “In the new constitution, the president and senate have all the executive and two thirds of the legislative power. In some weighty instances (as making all kinds of treaties which are to be the laws of the land) they have the whole legislative and executive powers. They jointly, appoint all officers civil and military, and they (the senate) try all impeachments either of their own members, or of the officers appointed by themselves. Is there not a most formidable combination of power thus created in a few, and can the most critic eye, if a candid one, discover responsibility in this potent corps?”

- The president and the senate are indirectly elected for four and six years respectively, which “is adduced to shew that responsibility is as little to be apprehended from amenability to constituents, as from the terror of impeachment. . . . You are, therefore, Sir, well warranted in saying, either a monarchy or aristocracy will be generated, perhaps the most grievous system of government may arise. It cannot be denied with truth, that this new constitution is, in first principles, highly and dangerously oligarchic; and it is a point agreed that a government of the few, is, of all governments, the worst.”

- The House of Representatives is the only “democratic” check and even it is “a mere shred or rag of representation: It being obvious to the least examination, that smallness of number and great comparative disparity of power, renders that house of little effect to promote good, or restrain bad government.”

- “But what is the power given to this ill constructed body? To judge of what may be for the general welfare, and such judgments when made, the acts of Congress become the supreme laws of the land. This seems a power co-extensive with every possible object of human legislation. Yet there is no restraint in form of a bill of rights, to secure (what Doctor Blackstone calls) that residuum of human rights, which is not intended to be given up to society, and which indeed is not necessary to be given for any good social purpose.” This would include the “rights of conscience, the freedom of the press, and the trial by jury.”

- “The impartial administration of justice, which secures both our persons and our properties, is the great end of civil society.” However, Lee, as shown above, believes the government under this constitution will become detached and oligarchic; consequently, if the “administration of justice” be “entirely entrusted to the magistracy, a select body of men, and those generally selected by the prince, or such as enjoy the highest offices of the state, these decisions in spite of their own natural integrity, will have frequently an involuntary bias towards those of their own rank and dignity. It is not to be expected from human nature, that the few should always be attentive to the good of the many. The learned judge further says, that every tribunal selected for the decision of facts, is a step towards establishing aristocracy; the most oppressive of all governments.”

Lee recognized that the "answer" to the objections raised is "that the new legislature may provide remedies." "But, as they may," Lee continued, "so they may not, and if they did, a succeeding assembly may repeal the provision. The evil is found resting upon constitutional bottom, and the remedy upon the mutable ground of legislation, revocable at any annual meeting."

[At this point, the most interesting parts of Lee’s letter are his views on sectionalism—so deadly by the 1860s—and an “active conspiracy of those who govern.”]

Sectionalism

In this congressional legislature, a bare majority of votes can enact commercial laws, so that the representatives of the seven northern states, as they will have a majority, can by law create the most oppressive monopoly upon the five southern states, whose circumstances and productions are essentially different from theirs, although not a single man of these voters are the representatives of, or amenable to the people of the southern states. Can such a set of men be, with the least color of truth called a representative of those they make laws for? It is supposed that the policy of the northern states will prevent such abuses. But how feeble, Sir, is policy when opposed to interest among trading people: And what is the restraint arising from policy? Why that we may be forced by abuse to become ship-builders! But how long will it be before a people of agriculture can produce ships sufficient to export such bulky commodities as ours, and of such extent; and if we had the ships, from whence are the seamen to come? 4000 of whom at least will be necessary in Virginia. In questions so liable to abuse, why was not the necessary vote put to two thirds of the members of the legislature? [italics are mine]

Active Conspiracy of those who Govern

It having been found from universal experience, that the most express declarations and reservations are necessary to protect the just rights and liberty of mankind from the silent, powerful and ever active conspiracy of those who govern; and it appearing to be the sense of the good people of America, by the various bills or declarations of rights whereon the government of the greater number of states are founded, that such precautions are necessary to restrain and regulate the exercise of the great powers given to rulers. In conformity with these principles, and from respect for the public sentiment on this subject, it is submitted . . .

[The rest of Lee’s letter outlines his thoughts and gives certain suggestions about a bill of rights, many of which found expression in our Amendments, and the processes of government administration.]