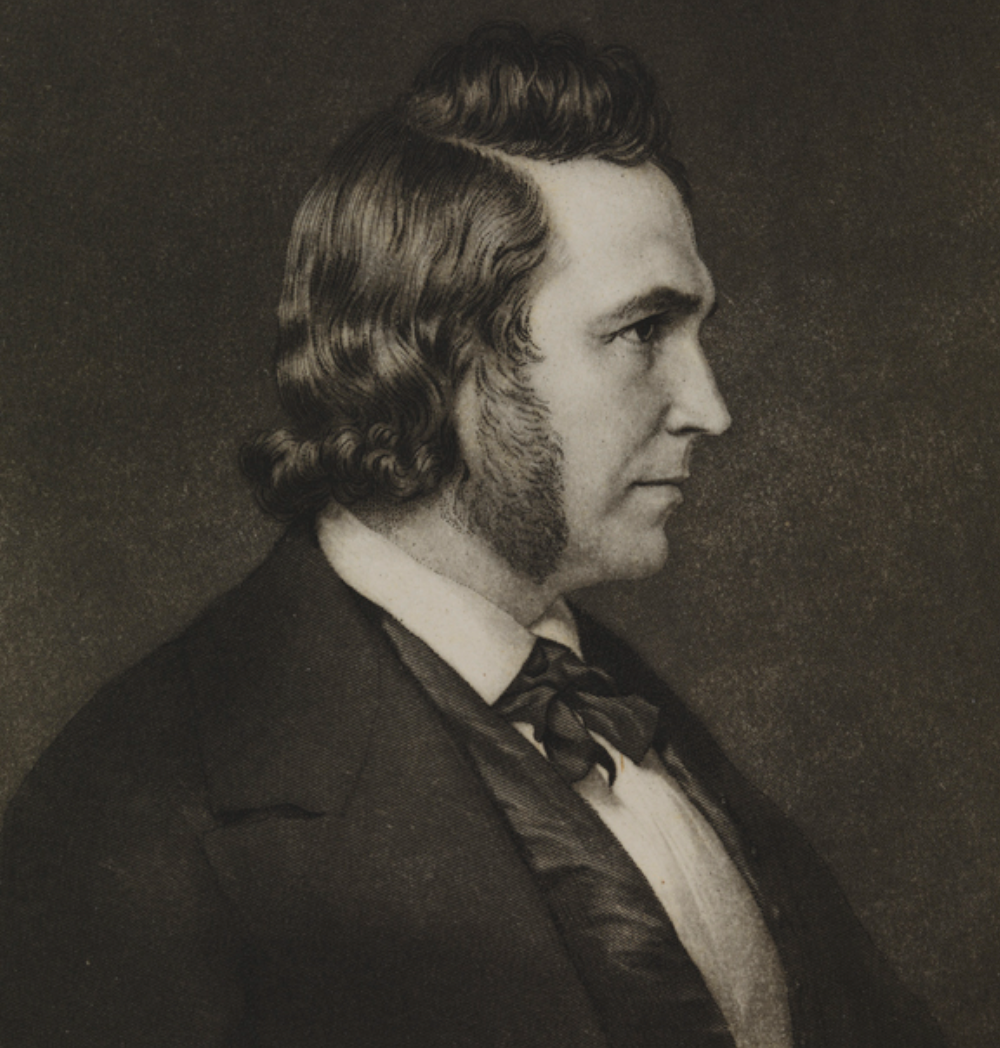

The Declaration of Independence: Thoughts on Application by C. Chauncey Burr, 1865

In this selection, Burr addresses what he sees as the practical application of the Declaration of Independence in the affairs of a "free people." In what way is the Declaration mere parchment versus real force in the political decisions of a body politic that no longer wishes to be connected?

The context of Burr's essay is the Civil War.

This is a thought-provoking piece and well worth the time for thinkers on such subjects as the meaning of the Declaration.

August Glen-James, editor

So, if it is self-evident that all men have inalienable rights, amongst which is the right of altering and abolishing one form of government and instituting another, laying its foundations on just such principles as they may think suited to secure the inalienable rights; then it is self-evident that, for so doing, the government has not the right to take their lives; unless it is urged that for using a self-evident right, there is a self-evident right of wholesale homicide.

We discuss the simple question of the right of a part of any free people to separate from the government, and to institute for themselves such a new government as they may think best suited to promote and secure their wants.

As our business is with principle, with the rights of men by virtue of the constitution of things, we have nothing to do with the motives, which might, at any time, have the power to induce a people to withdraw from a government, and make for themselves another one. Since these motives cannot be criminal, they may be wise or unwise, politic or impolitic. The motive cannot give qualities to the principle.

As the enumerated self-evident truths of the Declaration of Independence are just those which we have inferred from the constitution of man’s nature, and as they are conveniently stated, we propose employing them pretty freely in the discussions which follow.

We have noticed that men’s wants are inseparable qualities of their natures; that the rights belonging to them are inseparable from their wants; and the Declaration of Independence affirms, in substance, that the right to frame government, just as any people may think proper, is as unquestionable as are the rights, in view of which government is itself instituted. Indeed, it is not more self-evident that men have inalienable wants and rights, than it is that they have the right to frame just such a government as they may think proper for the gratification of the wants, and the protection and security of the rights. Natural political rights stand upon grounds exactly analogous to the natural and revealed religious rights of men. Both classes of rights belong to men by the creative work of God, and both are inseparable from them even beyond their own act, at any moment of their earthly existence. And as religious freedom consists in the use of the religious rights, just as the people may wish; so political freedom can consist alone in the use of political rights just as the people may wish. We take no half-way ground; but take the broad ground, which no human reason can successfully assail, that men’s right of self-government is self-evident and inalienable, at any moment of their earthly existence.

The only inducement to the formation of government is interest, and interest alone; and the only bond of its continuance is interest and interest alone. No man, subduing the boiling and blinding passions of ambition, malice, and undue self-love, and reflecting a little soberly, can fail to see the truth of this, with the clearness of powerful intuition. And any man denying the truth of it, and being consistent in the denial, is opposed to the doctrine of political freedom; and practicing the denial of it, consistent or not, in his intellectual conviction, his practice is that either of a despot or a tyrant. Now, if any two propositions claiming to be truths are necessarily self destructive, either the one, or the other, or both must be false. They cannot be both true. So, if it is self-evident that all men have inalienable rights, amongst which is the right of altering and abolishing one form of government and instituting another, laying its foundations on just such principles as they may think suited to secure the inalienable rights; then it is self-evident that, for so doing, the government has not the right to take their lives; unless it is urged that for using a self-evident right, there is a self-evident right of wholesale homicide. And this is murderous tyranny. Here now is just the trouble in our country. We do not higgle [archaic, haggle] at or mince the truth. The nation has adopted those fundamental political maxims, expressed in the Declaration of Independence, and founded on the intuitions of the human intellect, as laying the foundation of our whole political superstructure; and then it has adopted a rule of practice which must remain endlessly destructive of the very primal principles of freedom itself. We need not quote the Declaration of Independence at any length. The substance of it is that all men have certain self-evident, nay, too, inalienable, rights; one of which is “the right of the people to alter or abolish the government, and to institute a new government, laying its foundation on such principle, and organizing its powers in such form as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.”

And we need not pause to say that the declaration embodies a proposition logically universal. It is evident that it is universal, as universal as human wants, and as universal as the self-evident and inalienable rights of men. The most general words of language cannot make the declaration too general. Any people, at any time, in any government, either have the right to alter and abolish the government, and institute a new one, or the self-evident truths of human reason, as expressed in the political maxims which undergird our own form of government are self-evident falsehoods, frauds, and cheats. We do not mean the whole people have this right; but we mean, just as the language of the Declaration means, that a people forming a part of the whole people have the right—have it by the self-evident and inalienable endowment of God himself.

Now, if an act may be properly called a maxim, it is self-evident that the maxims in which the government has its life, and the maxim of using the sword, are mutually destructive of each other. They cannot harmonize together. If the people have the self-evident rights declared in the formula of all free governments, then the government has not the right to make war upon the people because they seek to employ the self-evident rights. And equally self-evident is it that the people have not the right of freedom, if the government has the right of coercion. To speak of a coerced people as a free people, is to speak contradiction and absurdity. The two things cannot subsist together. Coercion is but persecution turned against political freedom, instead of against religious freedom; for we have seen that both kinds of freedom are alike the inalienable gift of God, founded upon closely analogous principles, which are inseparable from our common humanity. And no man can show one solid reason for using the sword, in this connection, in the state, which cannot be used with equal force for its use in the church. In the one case, it is the symbolical, and too often the real, destroyer of civil liberty; in the other it is the destroyer of religious liberty. In both cases it has been but far too frequently the destroyer of both life and liberty; in no case, can it possibly be reconciled with either religious or political freedom.

If it is urged that, without the sword, government could not be maintained, we reply: first, men ought then to abandon these so-called self-evident political truths, as self-evident falsehoods; and to contend that men are self-evidently free, when they are bound in the manacles of coercion and political slavery. But, secondly: we answer that there is just as good ground for believing that government will be maintained as there is that it will be formed. Interest is the only conceivable inducement to its formation; and so long as interest remains, it will be an inducement to its continuance. If men are forced to remain under the government, after it ceases to promote their interests, and government has the right to coerce obedience, then it is too manifest to require argument that the people so coerced are abject slaves to a tyrant, if he professes to rule in the name of liberty. But, thirdly, if the lessons of all past time establish anything, they establish the fact that war has been the ravager and destroyer of the nations, rather than the preserver of them and their constitutions. We reply lastly, if there is not way of preserving government but by the appeal to the bloody arbitrament of the sword, then mankind would be a million times better off to abandon at once all government, and return to the simplest habits of nomadic life, under patriarchal governments, each family far removed from all others. For, as it is, civilization’s most striking characteristic is increased facilities for destroying people, with increased malice to employ the enginery of destruction. But the axiomatic principles of government perverted, the object of its institution wholly misconceived and abused, as might, in reason, be expected, it is supported by cruel means and false maxims.