The Difference Between Nullification and Secession: Thoughts by Jefferson Davis, 1881.

Nullification and secession were hot-button issues in the 19th century . . . and seemingly still are today. As power in Washington, D.C. oscillates from one party to the other, the elements in the ousted faction often saber rattles about secession and nullification.

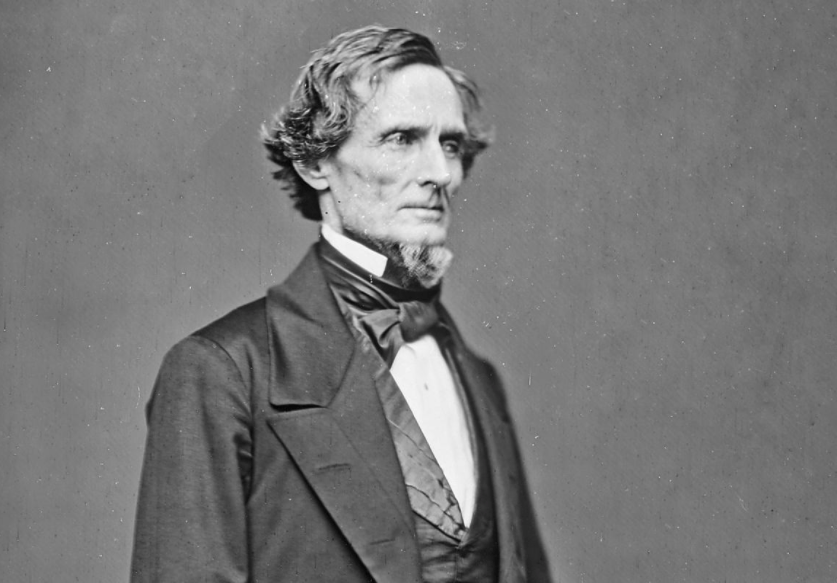

With this in mind, it may be interesting to some to read about how Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States, defined the two concepts.

August Glen-James, editor

Secession, on the other hand, was the assertion of the inalienable right of a people to change their government, whenever it ceased to fulfill the purpose for which it was ordained and established.

A little consideration of these plain and irrefutable truths [i.e., essentially, argued Davis, that a citizen owes paramount allegiance to the state, in its corporate capacity, in which (s)he resides--editor] would show how utterly unworthy and false are the vulgar taunts which attribute “treason” to those who, in the late secession of the Southern states, were loyal to the only sovereign entitled to their allegiance, and which still more absurdly prate of the violation of oaths to support “the government,” an oath which nobody ever could have been legally required to take, and which must have been ignorantly confounded with the prescribed oath to support the Constitution.

Nullification and secession are often erroneously treated as if they were one and the same thing. It is true that both ideas spring from the sovereign right of a state to interpose for the protection of its own people, but they are altogether unlike as to both their extent and the character of the means to be employed. The first was a temporary expedient, intended to restrain action until the question at issue could be submitted to a convention of the states. It was a remedy which its supporters sought to apply within the Union, a means to avoid the last resort—separation. If the application for a convention should fail, or if the state making it should suffer an adverse decision, the advocates of that remedy have not revealed what they proposed as the next step—supposing the infraction of the compact to have been of that character which, according to Webster, dissolved it.

Secession, on the other hand, was the assertion of the inalienable right of a people to change their government, whenever it ceased to fulfill the purpose for which it was ordained and established. Under our form of government, and the cardinal principles upon which it was founded, it should have been a peaceful remedy. The withdrawal of a state from league has no revolutionary or insurrectionary characteristic. The government of the state remains unchanged as to all internal affairs. It is only its external or confederate relations that are altered. To term this action of a sovereign a “rebellion,” is a gross abuse of language. So is the flippant phrase which speaks of it as an appeal to the “arbitrament of the sword.” In the late contest, in particular, there was no appeal by the seceding states to the arbitrament of arms. There was on their part no invitation nor provocation to war. They stood in an attitude of self-defence, and were attacked for merely exercising a right guaranteed by the original terms of the compact. They neither tendered nor accepted any challenge to the wager of battle. The man who defends his house against attack cannot with any propriety be said to have submitted the question of his right to it to the arbitrament of arms.

Two moral obligations or restrictions upon a seceding state certainly exist: in the first place, not to break up the partnership without good and sufficient cause; in the second, to make an equitable settlement with former associates, and, as fare as may be, to avoid the infliction of loss or damage upon any of them. Neither of these obligations was violated or neglected by the Southern states in their secession.