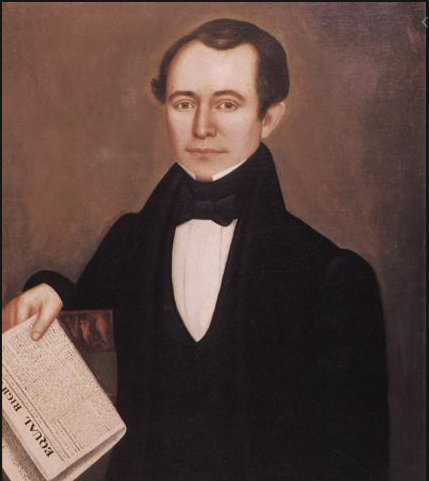

The Division of Parties, Thoughts by William Leggett, 1834

In this post, readers will recognize arguments that may seem eerily modern in may ways. From the very beginning, Americans have divided into parties and bickered over the nature and extent of the Federal government. Consequently, Leggett's characterization of the "Democracy" and the "Aristocracy" should present an interesting journey into the 1830s.

August Glen-James, editor

The privilege of self-government is one which the people will never be permitted to enjoy unmolested. Power and wealth are continually stealing from the many to the few. There is a class continually gaining ground in the community, who desire to monopolize the advantages of the Government, to hedge themselves round with exclusive privileges, and elevate themselves at the expense of the great body of the people. These, in our society, are emphatically the aristocracy . . .

Since the organization of the Government of the United States the people of this country have been divided into two great parties. One of these parties has undergone various changes of name; the other has continued steadfast alike to its appellation and to its principles, and is now, as it was at first, the Democracy. Both parties have ever contended for the same opposite ends which originally caused the division—whatever may have been, at different times, the particular means which furnished the immediate subject of dispute. The great object of the struggles of the Democracy has been to confine the action of the General Government within the limits marked out in the Constitution: the great object of the party opposed to the Democracy has ever been to overleap those boundaries, and give to the General Government greater powers and a wider field for their exercise. The doctrine of the one party is that all power not expressly and clearly delegated to the General Government, remains with the States and with the People: the doctrine of the other party is that the vigor and efficacy of the General Government should be strengthened by a free construction of its powers. The one party sees danger from the encroachments of the General Government; the other affects to see danger from the encroachments of the States.

This original line of separation between the two great political parties of the republic, though it existed under the old Confederation, and was distinctly marked in the controversy which preceded the formation and adoption of the present Constitution, was greatly widened and strengthened by the project of a National Bank, brought forward in 1791. This was the first great question which occurred under the new Constitution to test whether the provisions of that instrument were to be interpreted according to their strict and literal meaning; or whether they might be stretched to include objects and powers which had never been delegated to the General Government, and which consequently still resided with the states as separate sovereignties.

The proposition of the Bank was recommended by the Secretary of the Treasury on the ground that such an institution would be “of primary importance to the prosperous administration of the finances, and of the greatest utility in the operations connected with the support of public credit.” This scheme, then, as now, was opposed on various grounds; but the constitutional objection constituted then, as it does at the present day, the main reason of the uncompromising and invincible hostility of the democracy to the measure. They consider it as the exercise of a very important power which had never been given by the states or the people to the General Government, and which the General Government could not therefore exercise without being guilty of usurpation. Those who contended that the Government possessed the power, effected their immediate object; but the controversy still exists. And it is of no consequence to tell the democracy that it is now established by various precedents, and by decisions of the Supreme Court, that this power is fairly incidental to certain other powers expressly granted; for this is only telling them that the advocates of free construction have, at times, had the ascendancy in the Executive and Legislative, and, at all times, in the Judiciary department of the Government. The Bank question stands now on precisely the same footing that it originally did; it is now, as it was at first, a matter of controversy between the two great parties of this country—between parties as opposite as day and night—between parties which contend, one for the consolidation and enlargement of the powers of the General Government, and the other for strictly limiting that Government to objects for which it was instituted, and to the exercise of the means with which it was entrusted. The one party is for a popular Government; the other for an aristocracy. The one party is composed, in a great measure, of the farmers, mechanics, laborers, and other producers of the middling and Lower classes, (according to the common gradation by the scale of wealth,) and the other of the consumers, the rich, the proud, the privileged—of those who, if our Government were converted into an aristocracy, would become our dukes, lords, marquises and baronets. The question is still disputed between these two parties—it is ever a new question—and whether the democracy or the aristocracy shall succeed in the present struggle, the fight will be renewed, whenever the defeated party shall be again able to muster strength enough to take the field. The privilege of self-government is one which the people will never be permitted to enjoy unmolested. Power and wealth are continually stealing from the many to the few. There is a class continually gaining ground in the community, who desire to monopolize the advantages of the Government, to hedge themselves round with exclusive privileges, and elevate themselves at the expense of the great body of the people. These, in our society, are emphatically the aristocracy; and these, with all such as their means of persuasion, or corruption, or intimidation, can move to act with them, constitute the party which are now struggling against the democracy, for the perpetuation of an odious and dangerous moneyed institution.

Putting out of view, for the present, all other objections to the United States Bank,—that it is a monopoly, that it possesses enormous and overshadowing power, that it has been most corruptly managed, and that it is identified with political leaders to whom the people of the United States must ever be strongly opposed—the constitutional objection alone is an insurmountable objection to it.

The Government of the United States is a limited sovereignty. The powers which it may exercise are expressly enumerated in the Constitution. None not this stated, or that are not “necessary and proper” to carry those which are stated into effect, can be allowed to be exercised by it. The power to establish a bank is not expressly given; neither is incidental; since it cannot be shown to be “necessary” to carry the powers which are given, or any of them, into effect. That power cannot therefore be exercised without transcending the constitutional limits.

This is the democratic argument stated in its briefest form. The aristocratic argument in favor of the power is founded on the dangerous heresy that the Constitution says one thing, and means another. That necessary does not mean necessary, but simply convenient. By a mode of reasoning not looser than this it would be easy to prove that our Government ought to be changed into a Monarchy, Henry Clay crowned King, and the opposition members of the Senate made peers of the realm; and power, place and perquisites given to them and their heirs forever.