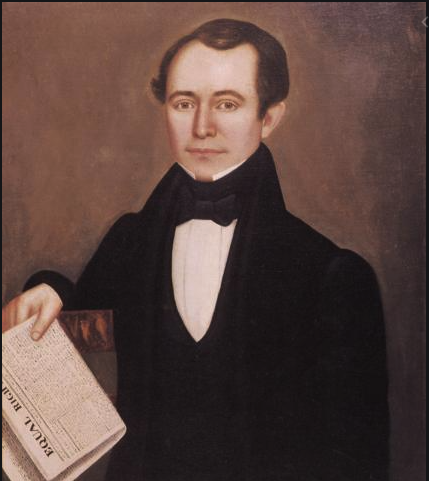

The French Treaty and National Honor: Thoughts by William Leggett, the "Evening Post," December 15, 1834.

During the Napoleonic Wars, American shipping had sustained losses for which the United States demanded compensation. A treaty was struck in July 1831 wherein the French were to pay 25 million francs in 6 annual installments which, for various political and organizational reasons, they failed to do. By early 1833, the non-payment of the debt began to created drama within the United States government. What should be done about the French default on the terms of the treaty?

Almost like clockwork, factionalism appeared in American politics: President Andrew Jackson, true to the form of a war hero, struck a strong tone:

"It is my conviction," said Jackson in his annual message to Congress, "that the United States ought to insist on a prompt execution of the treaty, and in case it be refused or longer delayed take redress into their own hands. After the delay on the part of France a quarter of a century in acknowledging these claims by treaty, it is not to be tolerated that another quarter of a century is to be wasted in negotiation about the payment. The laws of nations provide a remedy for such occasions. It is a well settled principle . . . that where one nation owes another a liquidated debt which it refuses to pay the aggrieved party may seize on the property belonging to the other . . . this remedy has been repeatedly resorted to, and recently by France herself toward Portugal under circumstances less questionable."

His political opponents, i.e., the Whigs, seized on Jackson's aggressive tone to politic about peace, money, and other themes in order to, ostensibly, undermine his position and gain political advantage.

This is the political atmosphere in which Leggett, a supporter of Jackson, wrote his piece. The entire editorial is interesting, but what follows is, I believe, the most interesting and relevant part of his position to modern readers.

August Glen-James, editor

While we ask nothing that is not clearly right, we will submit to nothing that is wrong. . . . But heaven grant that we may never have a full treasury. We desire to see no surplus revenue at the disposal of the Government, to be squandered in vast schemes of internal improvements, or prove an apple of discord to rouse the jealousy and enmity of the different sections of the country. If we have not the money in the treasury, we have it in the pockets of the people.

If we could compel France to pay us the debt at an expense of two or three millions, so that we might pocket one or two millions by the operation, these patriotic journals would applaud the undertaking. If we could make money by fighting, they would be the first to cry havoc! and let slip the dogs of war. But the idea of throwing money away for the more “bubble reputation,” seems to them exceedingly preposterous. National honor is a phrase to which they can attach no import by itself; it must be accompanied by the expression, national profit, to give it any significancy in their eyes.

We should like to know what opinion these worthies entertain of the conduct of those men who “plunged this country in all the horrors of war” on account of a preamble, to use Mr. Webster’s explanation of the matter. We allude to the authors of our revolution. It has never been supposed that they counted on making a great deal of money by the enterprise. They pledged their lives, their fortunes and their sacred honor on the issue—and life and fortune many of them forfeited; but none of them their honor! They entered into that contest expecting to endure great hardships, to make great sacrifices, the expend vast treasures, and for what? Not for the purposes of acquiring fifty millions of dollars from England, or five millions; bur for the simple acknowledgement of an abstract principle. It was enough for them that the principle of liberty was invaded. They did not wait until the consequences of the aggression should call for resistance. They thought, as Mr. Webster has truly and eloquently represented (though for an unhallowed purpose!) that “whether the consequences be prejudicial or not, if there be an illegal exercise of power, it is to be resisted.”

“We are not two wait” (let us borrow the language of a man whose words have the weight of law with the opponents of the President) “till great public mischiefs come; till the government is overthrown; or liberty itself put in extreme jeopardy. We should not be worthy sons of our fathers, were we so to regard great questions affecting the general freedom. Those fathers accomplished the Revolution on a strict question of principle. The Parliament of Great Britain asserted a right to tax the colonies in all cases whatsoever, and it was precisely on this question that they made the Revolution turn. The amount of taxation was trifling, but the claim itself was inconsistent with liberty; and that was, in their eyes enough. It was against the recital of an act of Parliament, rather than against any suffering under its enactments, that they took up arms. They went to war against a preamble. They fought seven years against a declaration. They poured out their treasures and their blood like water, in a contest, in opposition to an assertion, which those less sagacious, and not so well schooled in principles of civil liberty, would have regarded as barren phraseology, or mere parade of words. On this question of principle, while actual suffering was yet afar off, they raised their flag against a power to which, for purposes of foreign conquest and subjugation, Rome, in the height of her flory, is not to be compared; a Power which has dotted over the surface of the whole globe with her possessions and military posts; whose morning drum-beat, following the sun, and keeping company with the hours, circles the earth daily with one continuous and unbroken strain of the martial airs of England.” [Presumably Daniel Webster, editor]

Such was the cause for which our fathers fought, and such the power with which they battled. They were of that metal that on a question of honor or right they did not stop to count the cost. Their minds were throughly imbued with the sentiment, that

Rightly to be great

Is, not to stir without great argument,

But greatly to fine quarrel in a straw,

Where honor’s at the stake.

A portion of their descendants seem to be animated with very different principles. Those who but recently were ready for civil broil, who proclaimed that we were on the eve of a revolution, and on questions which involved mere difference of political opinion—questions which the peaceful weapon of suffrage was fully adequate to decide,—now start back with well-painted horror from the prospect of strife with a foreign nation, which, after having despoiled our citizens, and trifled with our government, through long years of patient intercession, has at last capped the climax of indignity by the grossest insult which can be offered to a sovereign people; namely, by the causeless violation of a solemn international pact. But it discovered that a war with that nation would be attended with expense, and therefore it ought not to be undertaken! Money, according to these journals, is of more value than honor. Let a foreign nation tread on you and spit on you, and bear it meekly, if it will const you money to avenge this insult! Such at least is the precept to be inferred from their remarks.

It is for the purpose of enforcing this precept, we presume, that the public have been treated, in various journals, with highly colored pictures of the evils of war. Our merchants have been represented as prostrated, our ships rotting at the wharves, our shores lighted with conflagrations, and the ocean incarnadined with slaughter. The tears of widows have streamed through the pens of these pathetic gentlemen, and the cries of orphans have been heard in the clatter of their presses. Pirates and marauders infest every line they write, and the thunders of a naval conflict roar in every paragraph. It is fortunate, however, that the reader can turn fro these dismal forebodings to the sober pages of history, and learn how far the truth, in relation to the past, sustains these fancy sketches of the future. What is the fact? We have passed through two wars with the most formidable power on earth, and yet survive, to prove to France, by force forms, if it should be necessary, that while we ask nothing that is not clearly right, we will submit to nothing that is wrong.

But if war must come of our asserting our rights, let it come! Much as we should regret, on various accounts, any collision with France, we would not avoid strife even with that country at the expense of national honor or justice. We are prepared for any event. True, certain members of Congress exclaimed with affected horror, “What! Plunge into war with an empty treasury!” But heaven grant that we may never have a full treasury. We desire to see no surplus revenue at the disposal of the Government, to be squandered in vast schemes of internal improvements, or prove an apple of discord to rouse the jealousy and enmity of the different sections of the country. If we have not the money in the treasury, we have it in the pockets of the people. Our wide and fruitful territory is loaded with abundance. Plenty smiles in every nook and corner of the land. The voice of thanksgiving ascends to heaven from the grateful hearts of millions of happy freemen. Our Government owes not one dollar of public debt, and its credit is unbounded, for its basis is the affections of the people, and its resources are coextensive with their wealth. Let it become necessary again for that Government to maintain its honor at the hazard of war, though it should even be “against a preamble,” and we shall again find that a people thoroughly imbued with the principle of liberty are ever ready to pledge their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor in support of such a quarrel.

We wish that journalists, who, beneath the scum and crust of party prejudices and passions have the true interest and glory of their country at heart, would adopt a similar tone—

“Let us appear not rash nor diffident:

Immoderate valour swells into a fault,

And fear admitted into public counsels,

Betrays like treason: let us shun them both.”