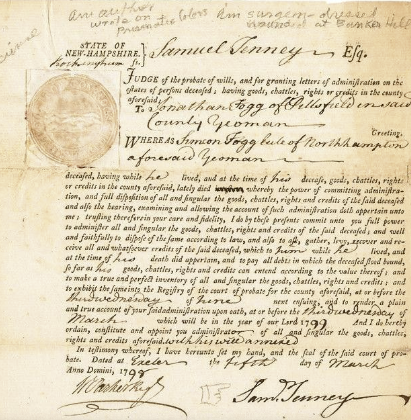

The Nature of the Union under the Proposed Constitution: Thoughts by Samuel Tenney, 1788, Writing as "Alfredus."

It is always central to historical literacy to apprehend how the generations who lived through and/or forged major historical events understood the various issues of such momentous times. The history surrounding the ratification of the Constitution of the United States is of particular interest since, over time, parties have formed and seem to have interpreted the Constitution in wildly different ways.

For instance, in contradistinction to the passage below, in the 1830s Joseph Story and Daniel Webster held, generally speaking, that the Constitution was ratified by the people of the several states at large, as a "country" or one people, rather than separately, as distinct political entities, via the individual states in their corporate capacity. This interpretation of the Constitution was used by Abraham Lincoln to deny the right of secession. The South, in general terms, held the polar opposite view the Constitution in the latter way outlined above.

Here are a couple of points to keep in mind while reading this excerpt: First, the "Bill of Rights" Tenney is writing about is not the Bill of Rights, written by Madison and added to the Constitution in 1791. Tenney is referencing the several bills of rights extant in the several states with the implication being that the Constitution, as a limited document of enumerated powers only, will not infringe.

Second, keep in mind that the Preamble of the Constitution, referenced by Tenney, contained what can only be seen as vague language, which was constantly pointed out by Anti-Federalist writers. What does "general welfare" actually entail? Who gets to decide what the "general welfare" requires? These questions are germane to the entire history of The United States under the Constitution.

August Glen-James, editor

It must therefore be taken for granted that every thing not expressly given up is retained by the states.

The Constitution now before the public is not a compact between individuals, but between several sovereign and independent political societies already formed and organized. These societies have general and particular interests and concerns. Those which respect the whole are submitted to the direction of the federal governments; while those which respect individual states only are left, as they ought to be, in the hands of the state assemblies. To prevent any interference between the federal and state governments, the objects of the former are pointed out in the preamble to the Constitution, viz. “To form a more perfect union—establish justice—insure domestic tranquility—provide for the common defense—promote the general welfare—and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and posterity.” These objects are all national and important. The powers vested in the supreme authority for the accomplishment of these purposes are accurately defined in the 8th section of the first article, and limited in the section following. It must therefore be taken for granted that every thing not expressly given up is retained by the states. If this is not enough to secure the liberties of the subject, The United States guarantee to each separate state a republican form of government. Of these, the Bill of Rights, where they have any prefixed, is an essential part; of consequence the Bill of Rights is as effectually secured by the Constitution proposed as if it had been expressly mentioned.