The Socialism of Deschamps: Analysis by Igor Shafarevich

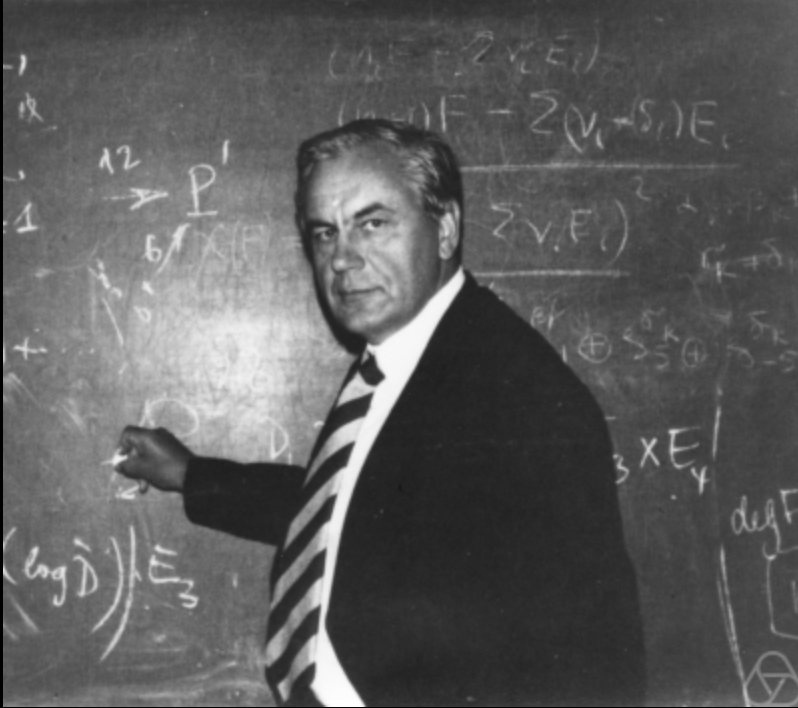

Igor Shafarevich (1923-2017) was a gifted Russian mathematician and Soviet dissident. He associated with some notable "trouble makers" in the USSR, like novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. One of Shafarevich's students, Ilya Piatetski-Shapiro, revealed that the math savant "disliked the October" and had "negative feelings for Communism. Though he felt political heat, his prowess as a mathematician seems to have protected him from the full forces of Soviet repression.

In his work, The Socialist Phenomenon, Shafarevich analyzed the varieties of collectivist thought throughout time, amongst cultures, and across continents. This post extracts a portion of thought from his section on “Chiliastic Socialism,” which included a chapter about The Socialism of the Philosophers from the Enlightenment. This post excerpts Shafarevich's summary of the Benedictine monk, Deschamps, who wrote Truth or the True System in the eighteenth century.

August Glen-James, editor

“Evil in man is present only due to the existing civil state, which endlessly contradicts man’s nature. There was no such evil in man when he was in a savage state.”

Deschamps is the author of one of the most striking and internally consistent socialist systems. He is a philosopher of the highest order, and is sometimes referred to as a precursor of Hegel. That is unquestionably correct, but while following a path similar to the one Hegel would take later, Deschamps also developed many concepts which were to be enunciated by Hegel’s disciples of the left—Feuerbach, Engles, and Marx. And in his conception of Nothingness he anticipates in many respects the contemporary existentialists.

Deschamps says: “The word ‘God’ must be eliminated from our languages.” Nevertheless, he was a passionate opponent of atheism. Of his system he has the following to say: “At first glance, it might be possible to think that it is a concise formulation of atheism, for all religion is destroyed in it. But upon consideration, it is impossible not to be convinced that it is not a formulation of atheism at all, for in the place of a rational and moral God (whom I do subject to destruction, for he merely resembles a man more powerful than other men) I set being in the metaphysical sense, which is the basis of morality that is far from arbitrary.”

“Everything is nothing. No doubt no one before me has ever written that everything and nothing are one and the same.” For Deschamps, this principle is basic to his doctrine on existence: “What is the cause of existence? Answer: Its cause resides in the fact that nothing is something, in that it is existence, in that it is everything.”

Here he finds a place for God as well:

“God is nothing, nonexistence itself.” Apparently, these principles, along with the deductions resulting from them, are what Deschamps opposes to atheism, which he declares a purely negative, destructive doctrine. He calls it the “atheism of cattle,” i.e., of beings who have not overcome religion, and who have not even developed to the level of religion.

To the negative character of the philosophes’ atheism Deschamps opposes what he sees as the positive character of his own system:

“The system I am proposing deprives us of the joys of paradise and the terror for hell—just like atheism—but, in contrast to atheism, it leaves no doubt as to the rightness of the destruction of hell and paradise. Beyond that, it gives us the supremely important conviction, which atheism does not and can never give, that for us paradise can exist only in one place, namely, in this world.”

Deschamps’s social and historical doctrine is based on metaphysics. It is derived from a conception of the evolution of mankind in the direction of the greatest manifestation of the idea on oneness, of totality.

“The idea of totality is equivalent to the idea of order, harmony, unity, equality, perfection. The condition of unity or the social condition derives from the idea of totality, which is itself unity and union; for purposes of their own well-being, people must live in a social condition.”

This mechanism of the evolution is the development of the social institutions which determine all other aspects of human life—language, religion, morality . . . . For example:

“It would be absurd to suppose that man came from the hands of God already mature, moral and possessing the ability to speak: speech developed along with society as it became what it is today.”

Deschamps considers various manifestations of evil to be the result of social conditions . . . . The social institutions themselves take shape under the influence of material factors such as the necessity of hunting in groups and the guarding of herds, as well as the advantages of man’s physical structure; in particular, that of his hand.

Deschamps divides the entire historical process into three stages or states through which mankind must pass:

“For man there exist only three states: the savage state or the state of the animals in the forest; the state of law—elsewhere Deschamps calls this the civil state—and the state of morals. The first is a state of disunity without unity, without society; the second state—ours—one of extreme disunity with unity, and the third is the state of unity without disunity. This last is without doubt the only state capable of providing people, insofar as this is possible, with strength and happiness.”

In the savage state people are much happier than in the state of law, in which contemporary civilized mankind lives:

“The state of law for us . . . is undoubtedly far worse than the savage state.” This is true with respect to contemporary primitive peoples: “We treat them with disdain, yet there is no doubt that their condition is far less irrational than ours.” But it is impossible for us to return to the savage state, which had to collapse and give birth to the state of law by force of objective causes—first and foremost, by the appearance of inequality, authority and private property.

Private property is the basic cause of all the vices inherent in the state of law: “The notions of thine and mine in relation to earthly blessings and women exist only under cover of our morals, giving birth to all the evil that sanctions these morals.”

The state of law, in Deschamps’s opinion, is the state of the greatest misfortune for the greatest number of people. Evil itself is considered an outgrowth of this state: “Evil in man is present only due to the existing civil state, which endlessly contradicts man’s nature. There was no such evil in man when he was in a savage state.”

But those very aspects of the state of law that make it especially unbearable prepare the transition to the state of morals which seems to be that paradise on earth about which Deschamps spoke in a passage quoted earlier. His description, replete with vivid detail, contains one of the most unique and consistent of socialist utopias.

All of life in the state of morals will be completely subordinated to one goal—the maximum implementation of the idea of equality and communality. People will live without mine and thine, all specialization will disappear, as will the division of labor.

“Women would be the common property of men, as men would be the common possession of women . . . Children would not belong to any particular man or woman.” “Women capable of giving suck and who were not pregnant would nurse all children without distinction . . . But how is it, you will object, that a woman is not to have her own children? No, indeed! What would she need that property for?” The author is not alarmed by the fact that such a way of life would lead to incest. “They say that incest goest against nature. But in fact it is merely against the nature of our morals.” All people “would know only society and would belong only to it, the sole proprietor.”

For transition into this state, much that is now considered of value would have to be destroyed, including “everything that we call beautiful works of art. This sacrifice would undoubtedly be a great one, but it would be necessary to make.” It is not only the arts—poetry, painting, architecture—that would have to disappear, but science and technology as well. People would no longer build ships or study the globe. “And why should they need the learning of a Copernicus, a Newton and a Cassini?”

Language will be simplified and much less rich, and people will begin to speak one stable and unchanging language. Writing will disappear, together with the tedious chore of learning to read and write. Children will not study at all and, instead, will learn everything they need to know by imitating their elders.

The necessity of thinking will also fall away: “In the savage state no one thought or reasoned, because no one needed to. In the state of law, one thinks and reasons because one needs to; in the state of morals, one will neither think nor reason because no one will have any need to do this any longer.” One of the most vivid illustrations of this change of consciousness will be the disappearance of all books. They will find a use in the only thing that they are in reality good for—lighting stoves. All books ever written had as their goal the preparation for the book which would prove their uselessness—Deschamps’s study. It will outlive the rest, but finally it, too, will be burned.

People’s lives will be simplified and made easier. They will scarcely use any metals; instead, almost everything will be made of wood. No large houses will be built and people will live in wooden huts. “Their furniture would consist only of benches, shelves and tables.” “Fresh straw, which would later be used as cattle litter, would serve them as a good bed on which they would all rest together, men and women, after having put to bed the aged and then children, would sleep separately.” Food would be primarily vegetarian and, thus, easy to prepare. “In their modest existence they would need to know very few things, and these would be just the things that are easy to learn.” This change of lifestyle is connected to fundamental psychic changes, which would tend to make “the inclination of each at the same time the common inclination.”

Individual ties between people and intense individual feeling would disappear. “There would be none of the vivid but fleeting sensations of the happy lover, the victorious hero, the ambitious man who had achieved his goal, or the laureled artist.” “All days would be alike.” And people would even come to resemble one another. “In the state of morals, no one would weep or laugh. All faces would be almost identical and would express satisfaction. In the eyes of men, all women would resemble all other women; and all men would be like all other men in the eyes of women!” People’s heads “will be as harmonious as they now are dissimilar.” “Much more than in our case, they would adhere to a similar mode of action in everything, and they would not conclude that this demonstrates a lack of reason or understanding, as we think about animals.”

This new society will give rise to a new world view. “And they would not doubt—and this would not frighten them in the least—that people, too, exist only as a result of the vicissitudes of life and someday are destined to perish as a consequence of the same vicissitudes and, perhaps, to be eventually reproduced once more by means of a transformation from one aspect to another.” “Because they, like us, would not take into account that they were dead earlier, that is, that their constituent parts did not exist in the past in human form; they would also, being more consistent than we, not place any significance on the termination of this existence in this form in the future.” “Their burials would not be distinguishable from those of cattle.” For: “their dead fellows would not mean more to them than dead cattle. . . . They would not be attached to any particular person sufficiently so that they would feel his death as a personal loss and mourn it.” “They would die a quiet death, a death that would resemble their lives.”