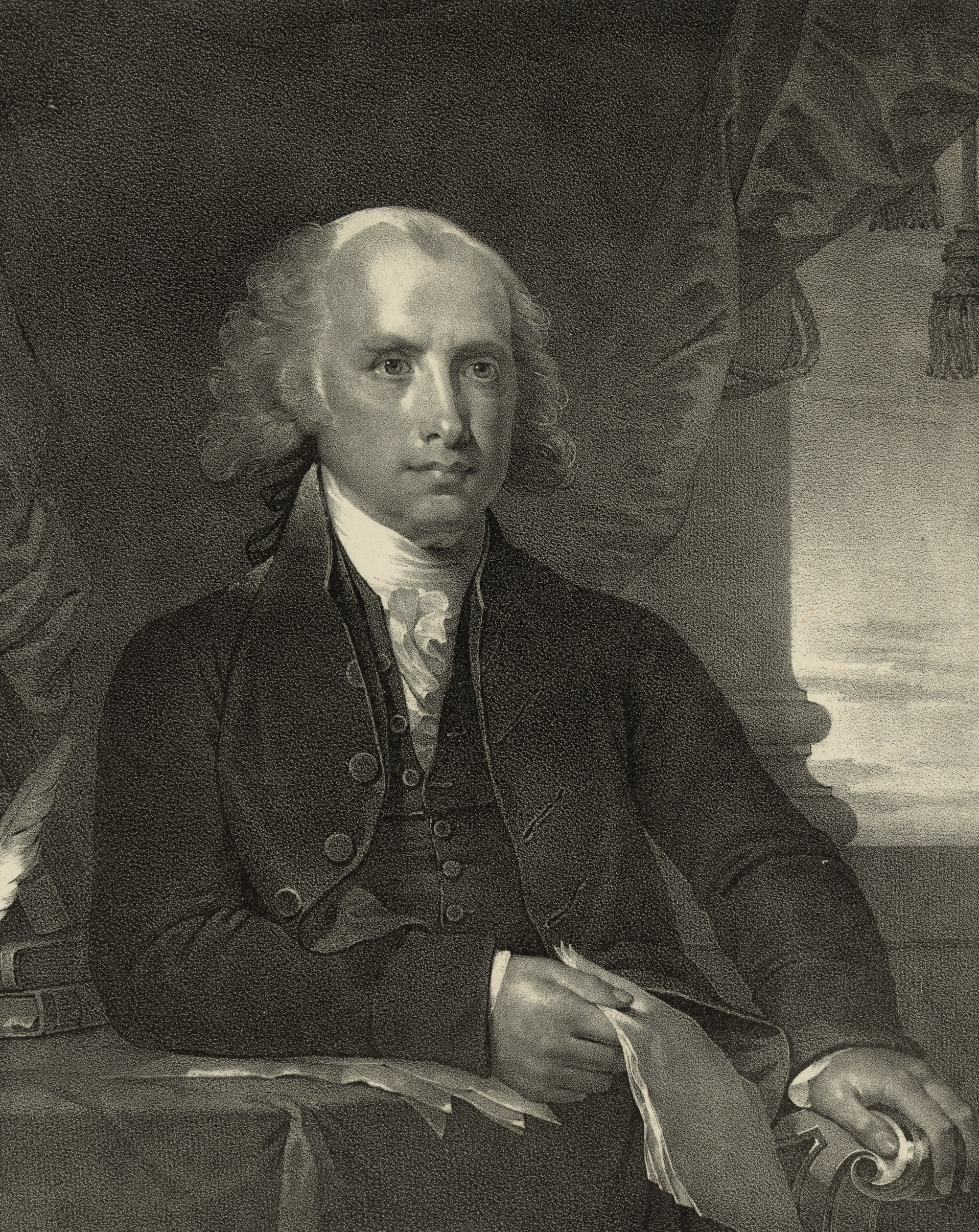

"The Spirit of Governments," Essay by James Madison for the "National Gazette," 18 February 1792--excerpt

“No government is perhaps reducible to a sole principle of operation,” Madison wrote. Rather, he theorized, “different and often heterogeneous principles mingle their influence in the administration” of government.

Madison’s essay for the National Gazette, from which this post comes, is in reference to Montesquieu’s assertion that fear, honor, and virtue are the great operative principles of, respectively, despotism, monarchy, and republics. Of course, Madison had his own take on Montesquieu, hence his reducibility claim from above, which he believed to be applicable to the condition of the United States. However, while paying due respect to Montesquieu, Madison wrote that the accuracy of the French writer’s argument “can never be defended against the criticisms which it has encountered.”

“Montesquieu was in politics,” Madison continued, “not a Newton or a Locke, who established immortal systems, the one in matter, the other in mind. He was in his particular science what Bacon was in universal science: He lifted the veil from the venerable errors which enslaved opinion and pointed the way to those luminous truths of which he had but a glimpse himself.”

The rest of Madison’s essay corrects, so to speak, Montesquieu’s view of the subject.

August Glen-James, editor

A government operating by corrupt influence; substituting the motive of private interest in place of public duty; converting its pecuniary dispensations into bounties to favorites or bribes to opponents

May not governments be properly divided, according to their predominant spirit and principles, into three species of which the following are examples?

First. A government operating by a permanent military force, which at once maintains the government and is maintained by it; which is at once the cause of burdens on the people and of submission in the people to their burdens. Such have been the governments under which human nature has groaned through every age. Such are the governments which still oppress it in almost every country of Europe, the quarter of the globe which calls itself the pattern of civilization and the pride of humanity.

Secondly. A government operating by corrupt influence; substituting the motive of private interest in place of public duty; converting its pecuniary dispensations into bounties to favorites or bribes to opponents; accommodating its measure to the avidity of a part of the nation instead of the benefit of the whole: in a word, enlisting an army of interested partizans, whose tongues, whose pens, whose intrigues, and whose active combinations, by supplying the terror of the sword, may support a real domination of the few under an apparent liberty of the many. Such a government, wherever to be found, is an imposter. It is happy for the new world that it is not on the west side of the Atlantic. It will be both happy and honorable for the United States if they never descend to mimic the costly pageantry of its form, nor betray themselves into the venal spirit of its administration.

Thirdly. A government deriving its energy from the will of the society, and operating by the reason of its measures on the understanding and interest of the society. Such is the government for which philosophy has been searching, and humanity been sighing, from the most remote ages. Such are the republican governments which it is the glory of America to have invented, and her unrivaled happiness to possess. May her glory be completed by every improvement on the theory which experience may teach; and her happiness be perpetuated by a system of administration corresponding with the purity of the theory.