The Virginia & Kentucky Resolves, 1798-99, By Madison and Jefferson--Extended Summary

Background:

Anticipating war with France, the Federalist-dominated congress (the Federalist party being led by Alexander Hamilton and John Adams) enacted, and President John Adams signed into law, four acts between June 18 and July 14, 1798 known as the Alien and Sedition Acts. The “alien” portion of the acts authorized the government to arrest, imprison, and deport any alien (i.e., non-citizen) who was subject to an enemy power during a time of war. This act also made it more difficult for immigrants to gain citizenship and, therefore, to vote.

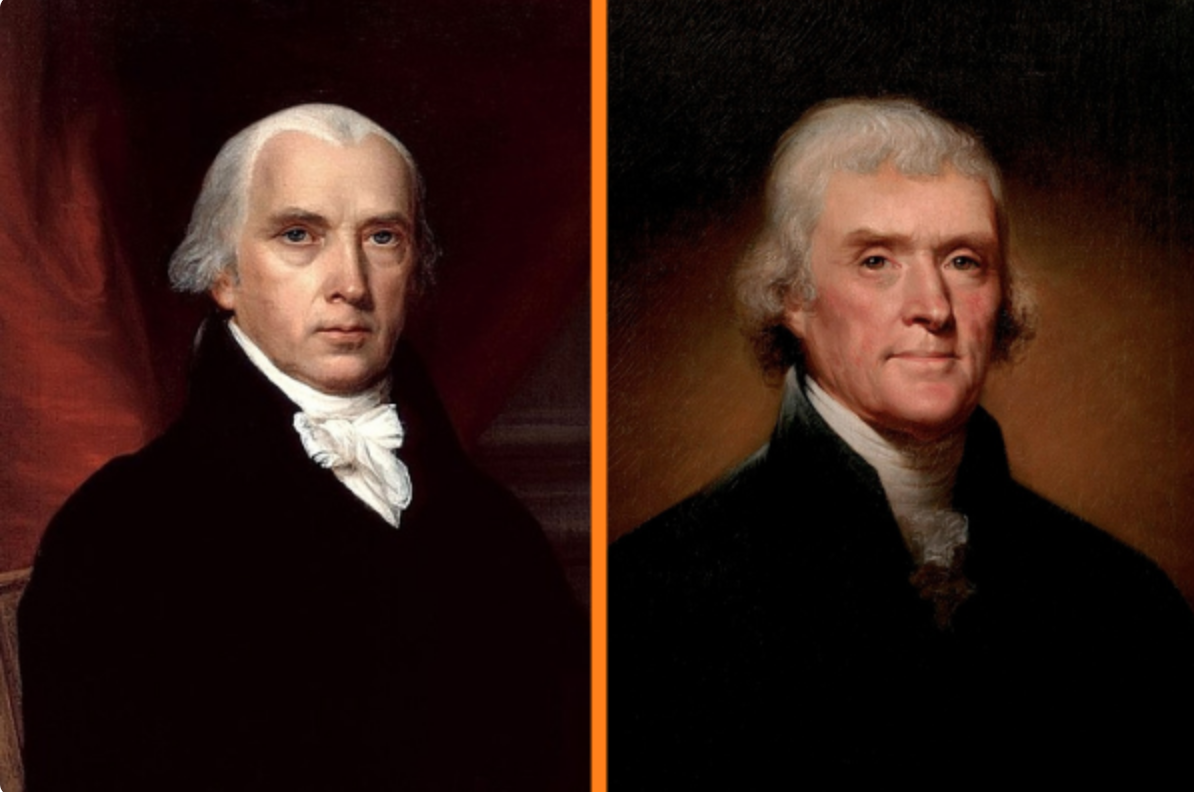

In the “sedition” portion of the acts, Federalists targeted their political foes, the Democratic-Republicans (led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison), with the Sedition Act. Hamilton and Adams believed that after being elected, office holders should not be criticized. Hence, the Act made it a treasonable offense for anyone who printed or declared any false, malicious, or scandalous writing or publication against Congress or the President of the United States.

Both Thomas Jefferson and James Madison opposed the Alien and Sedition Acts as unconstitutional and wrote against them, respectively, in the Kentucky Resolves and Virginia Resolves.

A summary of these Resolves highlighting the main ideas is the focus of this post.

August Glen-James, editor

That the several states who formed that instrument, being sovereign and independent, have the unquestionable right to judge of its infraction; and that a nullification, by those sovereignties, of all unauthorized acts done under colour of that instrument, is the rightful remedy. . . .

Virginia Resolves: Main Points

After expressing a “firm resolution to maintain and defend” both the Constitution of the United States and that of the State of Virginia “against every aggression either foreign or domestic,” Virginia, Madison wrote, had a “warm attachment to the Union of the States, to maintain which it pledges all its powers.” To that end, “it is their duty to watch over and oppose every infraction of those principles which constitute the only basis of that Union” which, “can alone secure its existence and the public happiness.”

Madison then outlined the basic origin and nature of the Federal government and the rights of the States.

- The powers of the federal government are the result of a compact, to which the states are parties

- The powers of the federal government are limited by the “plain sense and intention of the instrument constituting the compact [i.e., the Constitution]

- The federal government’s powers are “no further valid” than what is “authorized by the grants enumerated in that compact

- “In case of a deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of other powers, not granted by the said compact, the states who are parties thereto, have the right, and are in duty bound, to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining within their respective limits, the authorities, rights and liberties appertaining to them”

Next, Madison bemoaned that the federal government had “in sundry instances” tried to “enlarge its powers by forced constructions of the constitutional charter which defines them.” In particular, there seemed to be a design to “expound general phrases” that had been copied from the “very limited grant of power” in the Articles of Confederation “so as to destroy the meaning and effect, of the particular enumeration which necessarily” explained and limited said general phrases. The effect of this process, Madison wrote, would be to “consolidate the states by degrees, into one sovereignty,” which would “transform the present republican system of the United States, into an absolute, or at best a mixed monarchy.”

Madison continued:

That the General Assembly doth particularly protest against the palpable and alarming infractions of the Constitution, in the two late cases of the “Alien and Sedition Acts” passed at the last session of Congress; the first of which exercises a power nowhere delegated to the federal government, and which by uniting legislative and judicial powers to those of executive, subverts the general principles of free government; as well as the particular organization, and positive provisions of the federal constitution; and the other of which acts, exercises in like manner, a power not delegated by the constitution, but on the contrary, expressly and positively forbidden by one of the amendments thereto; a power, which more than any other, ought to produce universal alarm, because it is leveled against that right of freely examining public characters and measures, and of free communication among the people thereon, which has ever been justly deemed, the only effectual guardian of every other right.

That this state having by its Convention, which ratified the federal Constitution, expressly declared, that among other essential rights, “the Liberty of Conscience and of the Press cannot be cancelled, abridged, restrained, or modified by any authority of the United States,” and from its extreme anxiety to guard these rights from every possible attack of sophistry or ambition, having with other states, recommended an amendment for that purpose, which amendment was, in due time, annexed to the Constitution; it would mark a reproachable inconsistency, and criminal degeneracy, if an indifference were now shewn, to the most palpable violation of one of the Rights, thus declared and secured; and to the establishment of a precedent which may be fatal to the other.

Madison then closed the Resolution by appealing to their “brethren” of other states to join the General Assembly and “concur with this commonwealth in declaring, as it does hereby declare, that the acts aforesaid, are unconstitutional; and that the necessary and proper measures will be taken by each, for cooperating with this state, in maintaining the Authorities, Rights, and Liberties, reserved to this States respectively, or to the people.”

The Resolution was “Agreed to by the Senate, December 24, 1798.”

Kentucky Resolves: Main Points

In the Kentucky Resolves, Jefferson characterized the Alien and Sedition Laws as unconstitutional and obnoxious. Furthermore, he asserted that the “sundry” states that demurred from the Resolves used “unfounded suggestions, and uncandid insinuations, derogatory of the true character and principles of the good people of this commonwealth” in their opposition as a substitute for “fair reasoning and sound argument.” It would be “faithless . . . to themselves, and those they represent,” Jefferson wrote, to “acquiesce in principles and doctrines” asserted by their “sister states” in response to the Alien and Sedition Laws.

Jefferson continued thusly:

Our opinions of those alarming measures of the general government, together with our reasons for those opinions, were detailed with decency and with temper, and submitted to the discussion and judgment of our fellow citizens throughout the Union. Whether the decency and temper have been observed in the answers of most of those states who have denied or attempted to obviate the great truths contained in those resolutions, we have now only to submit to a candid world. Faithful to the true principles of the federal union, unconscious of any designs to disturb the harmony of that Union, and anxious only to escape the fangs of despotism, the good people of this commonwealth are regardless of censure or calumniation.

Jefferson then expostulated in the following manner:

RESOLVED, That this commonwealth considers the federal union, upon the terms and for the purposes specified in the late compact, as conducive to the liberty and happiness of the several states: That it does now unequivocally declare its attachment to the Union, and to that compact, agreeable to its obvious and real intention, and will be among the last to seek its dissolution: That if those who administer the general government be permitted to transgress the limits fixed by that compact, by a total disregard to the special delegations of power therein contained, annihilation of the state governments, and the erection upon their ruins, of a general consolidated government, will be the inevitable consequence: That the principle and construction contended for by sundry of the state legislatures, that the general government is the exclusive judge of the extent of the powers delegated to it, stop nothing short of despotism; since the discretion of those who administer the government, and not the constitution, would be the measure of their powers: That the several states who formed that instrument, being sovereign and independent, have the unquestionable right to judge of its infraction; and that a nullification, by those sovereignties, of all unauthorized acts done under colour of that instrument, is the rightful remedy: [bold-face added, editor] That this commonwealth does upon the most deliberate reconsideration declare, that the said alien and sedition laws, are in their opinion, palpable violations of the said constitution; and however cheerfully it may be disposed to surrender its opinion to a majority of its sister states in matters of ordinary or doubtful policy; yet, in momentous regulations like the present, which so vitally wound the best rights of the citizen, it would consider a silent acquiescence as highly criminal: That although this commonwealth as a party to the federal compact; will bow to the laws of the Union, yet it does at the same time declare, that it will not now, nor ever hereafter, cease to oppose in a constitutional manner, every attempt from what quarter soever offered, to violate that compact:

AND FINALLY, in order that no pretexts or arguments may be drawn from a supposed acquiescence on the part of this commonwealth in the constitutionality of those laws, and be thereby used as precedents for similar future violations of federal compact; this commonwealth does now enter against them, its SOLEMN PROTEST.

Approved December 3rd, 1799.