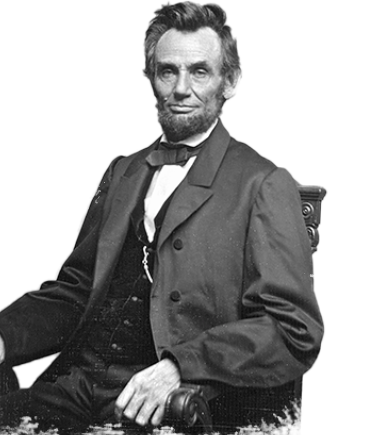

Lincoln's Proposed Amendment about Slavery, 1862

Interestingly, in his annual message to Congress, December 1, 1862, Abraham Lincoln proposed an amendment to the Constitution dealing with the slavery issue. Below is a summary of the main articles with additional quotes and analyses.

August Glen-James, editor

[1] Art.—Every State wherein slavery now exists which shall abolish the same therein at any time or times before the 1st day of January, A.D. 1900, shall receive compensation from the United States . . . .

Analysis: Lincoln believed that the length of time given to free the slaves, per this article, would mitigate the “sudden derangement” and the “vagrant destitution which must largely attend immediate emancipation” of a people destitute of land or means of support. The amendment, furthermore, would be cheaper and “more easily paid” over time than to continue an expensive war. “In a word,” Lincoln said, “it shows that a dollar will be much harder to pay for the war than will be a dollar for emancipation on the proposed plan. And then the latter will cost no blood, no precious life. It will be a saving of both.”

Lincoln also said:

In a certain sense the liberation of slaves is the destruction of property—property acquired by descent or purchase, the same as any other property. It is no less true for having been often said that the people of the South are not more responsible for the original introduction of this property than are the people of the North; and when it is remembered how unhesitatingly we all use cotton and sugar and share the profits of dealing in them, it may not be quite safe to say that the South has been more responsible than the North for its continuance. If, then, for a common object this property is to be sacrificed, is it not just that it be done at a common charge?

[2] Art.—All slaves who shall have enjoyed actual freedom by the chances of war at any time before the end of the rebellion shall be forever free; but all owners of such who shall not have been disloyal shall be compensated for them at the same rates as is provided for stated adopting abolishment of slavery, but in such [a] way that no slave shall be twice accounted for.

Analysis: In support of this article, Lincoln thought “it would be impracticable to return to bondage the class of persons therein contemplated.” Lincoln continued, “Some of them, doubtless, in the property sense belong to loyal owners, and hence provision is made in this article for compensating such.”

[3] Art.—Congress may appropriate money and otherwise provide for colonizing free colored persons with their own consent at any place or places without the United States.

Analysis: In support of this article, Lincoln said that “It does not oblige, but merely authorizes Congress to aid in colonizing such as may consent.” However, he emphasized:

I can not make it better known than it already is that I strongly favor colonization; and yet I wish to say there is an objection urged against free colored persons remaining in the country which is largely imaginary, if not sometimes malicious. It is insisted that their presence would injure and displace white labor and white laborers. . . . Is it true, then, that colored people can displace any more white labor by being free than by remaining slaves? If they stay in their old places, they jostle no white laborers; if they leave their old places, they leave them open to white laborers. . . . Emancipation, even without deportation, would probably enhance the wages of white labor, and very surely would not reduce them. . . . Labor is like any other commodity in the market--increase the demand for it and you increase the price of it. Reduce the supply of black labor by colonizing the black laborer out of the country, and by precisely so much you increase the demand for and wages of white labor.

But it is dreaded that the freed people will swarm forth and cover the whole land. . . . But why should emancipation South send the free people North? People of any color seldom run unless there be something to run from. Heretofore colored people to some extent have fled North from bondage, and now, perhaps, from both bondage and destitution. But if gradual emancipation and deportation be adopted, they will have neither to flee from. Their old masters will give them wages at least until new laborers can be procured, and the freedmen in turn will gladly give their labor for the wages till new homes can be found for them in congenial climes and with people of their own blood and race. . . . And in any event, can not the North decide for itself whether to receive them?